Experience the unique vision and invention of prolific artist and pioneer of contemporary printmaking and sculpture Kiki Smith.

Kiki Smith (b. 1954, Nuremberg, Germany, lives and works in New York, USA) has created a materially experimental and multifaceted body of work that explores the political and social aspects of human nature. This much-anticipated exhibition is her first solo UK exhibition in a public institution in 20 years.

This retrospective exhibition, organised in close collaboration with the artist, focusses on three distinctive areas of Smith’s practice: small sculptures created from the mid-1980s to present day; a selection from her printmaking, and the intricate Jacquard tapestries produced since 2012.

This exhibition is free, no booking required.

“A compelling show that pays tribute to the power of the human imagination.”

Her early small sculptures tackle bodily taboos such as decay, intimacy, mortality and physical pain. Smith says that she chose the human body as a subject because ‘it is the one form we all share’ and there is a poignant universality of experience in these sculptures of the human form fashioned from bronze, porcelain and crystal amongst many other materials.

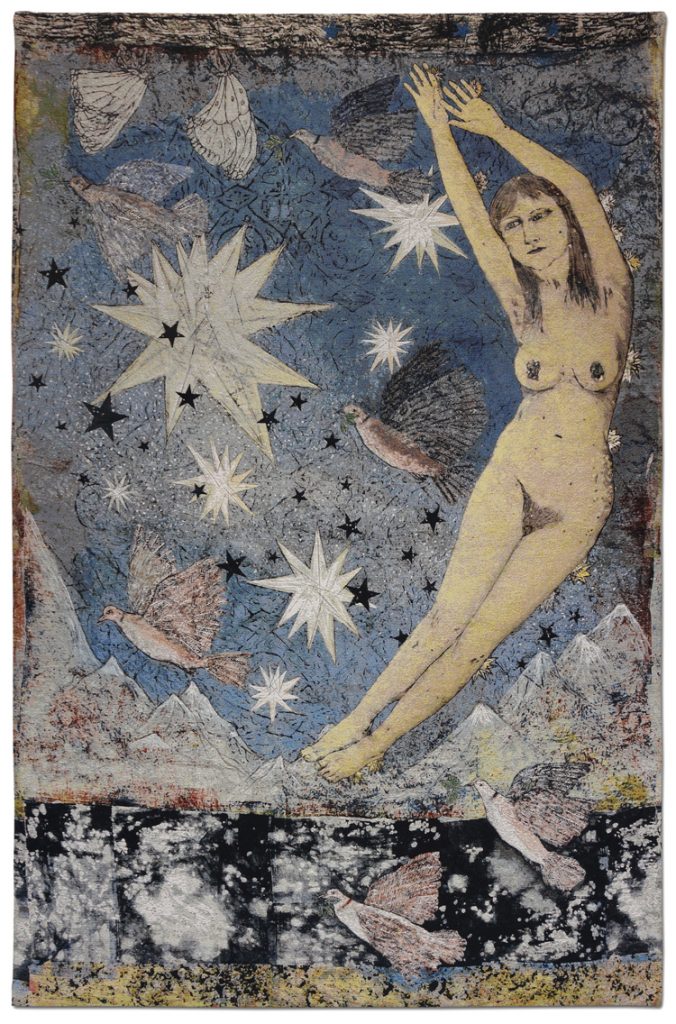

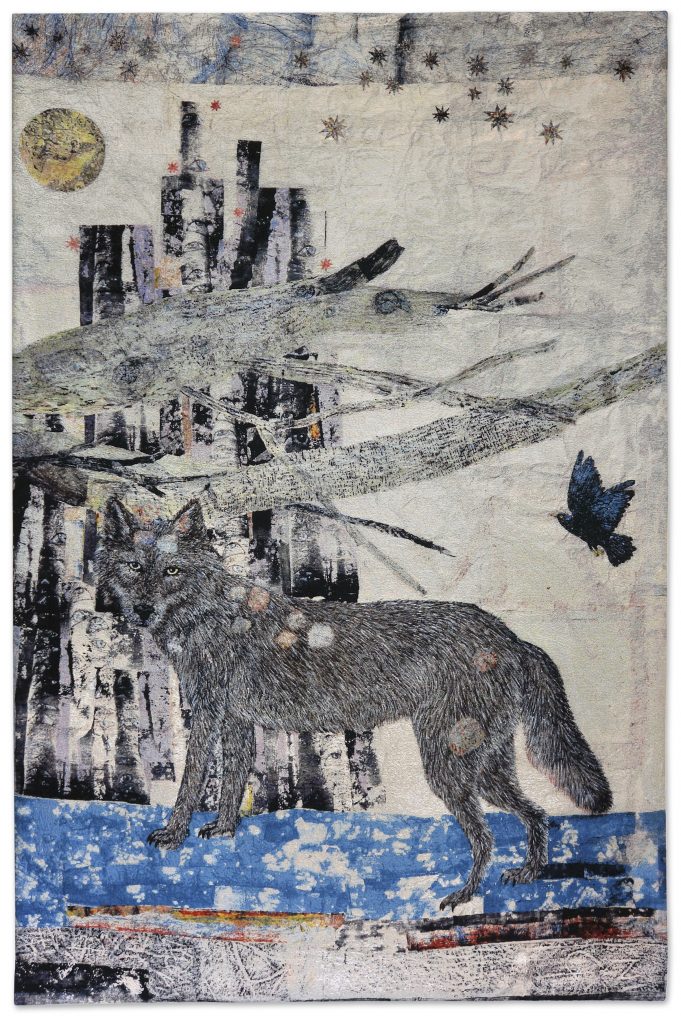

In the early 1990s Smith began depicting the natural world, starting with birds, and her art grew more mythological and folkloric. In these works, a menagerie of real and mystical creatures, delicate plants and shooting stars are presented to us in an astonishing abundance of materials. Endlessly inventive, Smith has fashioned animal assortments in bronze, shells from gold, frogs from coloured glass, birds from beads, sea creatures from ink and flowers from precious silver. Exquisitely detailed etchings and drawings can also be seen alongside large-scale tapestries depicting empowered goddesses travelling through wild forests and starlit skies.

‘I am a wanderer’, Kiki Smith says, and as she roams she collects inspiration from a myriad of sources and cultures. Those looking at her art are transported with her to a multitude of lands and epochs, discovering new forms, materials and stories as they follow her wondrous journey.

Kiki Smith: I am a Wanderer is curated by Petra Giloy-Hirtz.

Virtual Exhibition – Kiki Smith: I am a Wanderer

“Finally, this type of armchair gallery going has reached the point where it is really effective. I highly recommend this.” – Antonia Cunliffe, That’s Not My Age

Enter I am a Wanderer online and discover new insights in Kiki Smith’s works with short videos, behind-the-scenes moments, curator’s notes, children’s activities and more.

Kiki Smith was born in 1954 in Nuremberg, Germany, before her family moved to the United States in 1955. The daughter of the American actress and opera singer Jane Lawrence and the architect, painter and Abstract Expressionist sculptor Tony Smith (1912–1980), she grew up in an artistic environment which informed her sense of possibility.

Virtually self-taught, Smith describes herself as a “thing-maker.” In the 1970s she was drawn to representational art because when she moved to New York at that time many artists were interested in figuration. Around 1978, she joined Collaborative Projects, Inc. (Colab), an artists’ collective devoted to making art accessible through exhibitions outside commercial gallery settings. It was during this period that she made her first artworks, monotypes and drawings of everyday objects.

Kiki Smith’s works explore emotional states such as fear and dissonance as well as existential responses to being in the world. Her attention to themes of death and mortality evolved from her own life experience. Her father died in 1980 and in the late 1980s, Kiki Smith’s younger sister died from an AIDS-related illness, along with many of her colleagues from the art community.

Kiki Smith had her first solo exhibition in 1988 at the Fawbush Gallery in New York, and her first one-person museum show in 1989 at the Dallas Museum of Art, followed by her first European exhibition at the Centre d’art Contemporain in Geneva in 1990. In 1991, she was included in the Whitney Biennial in New York for the first time. Many exhibitions followed, especially in the United States, a prominent one among them being the retrospective Kiki Smith: A Gathering, 1980–2005, which opened at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, then toured throughout 2005–06. In New York, the Museum of Modern Art presented Prints, Books and Things in 2003. The great appreciation for Kiki Smith’s work in Europe is demonstrated by exhibitions such as that at the Kunstverein Bonn (1992), the Fondazione Querini Stampalia in Venice (2005), and the Palais des Papesses in Avignon (2013). Her work has been part of the Viva Arte Viva exhibition at the 57th Venice Art Biennale (2017), and her exhibition Procession was first shown at Haus der Kunst, Munich in 2018.

Her work is included in several public collections including Centre Pompidou in Paris, Museum of Modern Art in New York, Moderna Museet in Stockholm, Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, the Museum of Contemporary Art in San Diego, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, Tate Gallery in London, The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, Victoria and Albert Museum in London, and Whitney Museum of American Art in New York among many others.

Kiki Smith is an adjunct professor at NYU and Columbia University. She lives and works in New York City and Upstate New York.

“I do see a path of subject matter in my work – I went from the microscopic organs to systems to bodies to the religious body to cosmologies […] But that’s only in retrospect. At the time it’s more that certain materials interest you, and you go in that direction.” – Kiki Smith, 1997.

This exhibition’s selection of works was generated in close collaboration with the artist, and in dialogue with the city of Oxford, its medieval heritage, historic museum collections and strong tradition of fantastical literature, exemplified by C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien and Lewis Carroll. The city is the perfect host for an exhibition so rich in storytelling and mythology, in which Kiki Smith unfurls an entire world populated by beings of different cultures in time and space, foreign as well as familiar ones: female figures in particular, hybrid creatures, animals of all kinds, plants and heavenly bodies in a variety of forms and materials.

The interdisciplinary and collaborative spirit of Smith’s work across a rich variety of media, printmaking in particular, creates an interesting parallel with the arts and science context of Oxford’s renowned research culture. The political urgency of the artist’s work is equally expressed through a visual and material solidarity with marginalised beings and the natural environment. Smith continually portrays the connection between animals and humans in new configurations, emphasising friendship, survival, and protection. Her modern ‘bestiary’ (a medieval compendium of beasts) comes to life, to convey a sincere and timely message. Smith says: ‘We are interdependent with the natural world… our identity is completely attached to our relationship with our habitat and animals. I make things from images that catch my attention.’ In the manner of a subtle, poetic environmentalist, Smith communicates through art and beauty to remind us that it is mutual respect between humanity and nature that will secure the survival of both, and the planet as a whole.

Kiki Smith’s childhood in New Jersey was shaped by the intellectual and artistic milieu of her parents, opera singer Jane Lawrence and architect, painter, and sculptor Tony Smith, an important figure of Abstract Expressionism and Minimalism. Instead of the Minimal emphasis on the reduction of forms, the asceticism of the materials, and the banishment of emotion, historical context, and pathos, in Kiki Smith’s art feelings come to the fore: emotional states such as fear, dissonance and trauma.

Her inspiration has always derived from daily life and everyday experiences. As the artist explains: ‘I moved to the Lower East Side of New York City in 1976. The late 1970s and 80s was a moment of romantic enthrallment with sex, drugs and rock and roll, but also the time of the United States’ covert and overt military aggression in Central America. I began using images of bodies in an effort to find a language for my own discomfort and anxiety.’

Smith’s early artworks were influenced by the incredible political, social and cultural changes of this time, as shaped by the AIDS crisis, discourse on sexual identity and social gender, and feminist activism. She focuses on content and meaning, on existential questions and answers in direct response to the world. The artist investigates the human body without fear of taboos, humiliation, or the constraints of shame, engaging with the human condition. Her works tackle the subjects of age, dying and death, pain and healing, reanimation, wholeness and fragmentation, birth, sexuality, gender, identity and memory, as well as the ecological crisis of the planet. In the early 1990s, Smith began to incorporate history, mythology, legends and fairy tales into her work as well as elements of religion.

Her first sculptures were dedicated to parts of the body such as disembodied arms and fingers. By the mid-1980s, the artist seemed to dissect the entire human anatomy (using knowledge from training as an Emergency Medical Technician alongside her sister Beatrice in 1985), first drawing individual organs and then casting sculptures of them in bronze. She later returns to a focus on the body’s outer appearance, initially through soft materials such as gampi paper in 1987, and finally reproduces the human figure in its entirety in a life-size sculpture made of beeswax in 1991. Some of these full-scale wax sculptures from the 1990s are captured by Smith’s photography in her studio. Their perspectives and extreme close-ups render the sculptures’ status as objects or people uncertain. The blurry depths of field and other snapshot-like visual markers indicate Smith’s investigative use of photography to interrogate the afterlives of her sculptural practice.

In the Middle Galleries we encounter a Wünderkammer, ‘a cabinet of curiosities’ containing a myriad of forms and materials, both human and animal. The artist began making these multiples (limited series of identical objects, often cast) around 1980. Compelling evocations of the body – often dissected or disembodied – can be seen in this abundance of Kiki Smith’s material experimentation, from bronze, plaster, glass and porcelain to papier mâché, resin, cast silver and gold leaf – demonstrating her constant curiosity. A collection of hybrid creatures and natural phenomena are also displayed including a glass frog, a porcelain dead cat, a silver shooting star and a bat cast in bronze with piercing ruby eyes.

‘I am a wanderer,’ Kiki Smith says. And indeed, she is a wanderer through time and space, making ‘contact’ on a decades-long imaginary journey that takes her through foreign cultures. With the wanderlust of a cultural anthropologist she roams through lands and historical epochs, collecting and preserving the heritage of our collective memory. The artist herself speaks of the possibilities of ‘resurrection’ and ‘regeneration’, creating visions of beauty, reconciliation and hope in a dystopian world, communicating both poetic sensibility and appeal for action.

This exhibition is curated by Petra Giloy-Hirtz.

“The first works are based on the facets of the body, then I become more overt about languages of craft and decorative arts.” – Kiki Smith, 1997

Upper Gallery Tapestries:

During the intensive four-year process of making this body of woven works, it was important to Smith that the tapestries were made on the same scale as her original printed and collaged compositions (the cartoons), to retain the intimacy and textures of the work as initially conceived. As she explains: ‘It’s important that each scale has its own integrity.’ Some of the same imagery from her 12 tapestries has also been used to make works in stained glass and ceramic tiles.

Middle 1 Gallery Small Sculptures:

As an artist Kiki Smith embraces collaboration with skilled craftspeople and utilises many artisan techniques in her multiple-edition small sculptures, including glassblowing, casting, and working with delicate and complicated materials including porcelain, bronze, silver and papier-mâché. Smith makes many of her three-dimensional works initially on this intimate scale. They are then scanned – thanks to recent developments in technology – to produce larger cast sculptures, often intended for outdoor settings.

Middle 1 and 2 Galleries Photographs:

In some instances, Smith’s photographs document a work in progress to help the artist gain a sense of a work’s final emotional impact. In others, she records and interrogates different perspectives on a sculpture long after its completion. Some of these photographs give an insight into the making of Smith’s major installations from the mid-1990s, including the multiple bronze casts of dead birds in Jersey Crows, 1995. She will often photograph a detail – such as a pair of severed crow’s feet – so that it takes on the treasured status of a religious relic; a fragment standing in for the whole. There is frequently a degree of abstraction and alienation at work in her photography: for example, the life-size wax cast of a body in the foetal position is captured from the back at an angle, creating an entirely new experience of the sculpture.

Piper Gallery Prints:

Kiki Smith says of printmaking that ‘it has a technical aspect to it, and also endless amounts of freedom.’ She is equally interested by the mechanical properties of prints and the collaboration it takes to produce them: ‘I like that your mark is distanced, it gives you something that your own hand can’t, even though it comes from your hand.’

In the late 1990s, Smith discovered that etching was particularly well suited to capturing the feel and texture of fur, hair, feathers and other complex surfaces that cover both animal and human bodies. To make her prints of animals, Smith has drawn directly from her own pets, such as her cat, Ginzer, after his death. Like many of her studies from the natural world, the final image of Ginzer is uncertain in its possible suspension between life and death, a sombre memorial that is also a celebration of the close relationship between animals and humans.