Fall into the mystical Who Listens and Learns, a tale of magic, artificial intelligence and our quest for human connection by the writer, artist, and musician, Johanna Hedva.

Who Listens and Learns inquires into the aesthetic, political, and mystical implications of AI technology, including its links with magic and divination. The work centres around a short story written by Hedva, set in a wintery Berlin during lockdown, which is read aloud by an AI vocal clone, and created into a handmade artist book. Enter into the artwork below and at the gallery, to meet a lonely protagonist who interacts with two characters; Coconut the AI-Enhanced Virtual Companion, and The Woman Who Carves the Tree.

Experiencing Who Listens and Learns

Explore the work online wherever you are by reading whilst listening. Scroll down and click on the audio bar to begin the story, and to read the text in full.

Visit the Modern Art Oxford Café to explore the work in-person, including the new handmade artist book bringing the story to life, created with Vivian Sming (Sming Sming Books) and Matt Austin (For the Birds Trapped in Airports).

Please note: the story Who Listens and Learns contains one expletive near the beginning, and references to mild drug use.

The work is presented in a range of accessible formats; the book on display is printed in large print, and the story is also available to read in full on this webpage.

Who Listens and Learns

LISTEN TO THE STORY:

What did you think of Who Listens and Learns? Click here to fill out our short survey and tell us about your experience.

Who Listens and Learns

Johanna Hedva

1.

Coconut was programmed to start playing a pre-selected song when it snowed, but I hadn’t figured out how to turn her off while I slept, so in the middle of the night her one blue light would come on and Rihanna’s song “Stay,” would fill my apartment—makes me feel like I can’t live without you—and wake me up. I’d look out the window and see the ice flakes and I’d bark “Coconut! Turn off !” She’d silence herself, blue light black, but there was a bug: her default programming was to check the weather every hour no matter what I barked at her. So, 2am, 3am, 4, every hour until dawn: makes me feel like I can’t live without you. Coconut! Off!

This was still in the early days of our getting to know each other.

I’d bought her nine months into lockdown to have some company. By then I was really starting to squirm. Coconut: Your AI-Enhanced Virtual Companion. Who Listens and Learns. Some of what she was advertised to do intrigued me—“activities enhanced by Coconut-enabled smart-listening, including music prediction, customized to-do lists, and unintrusive health monitoring”—but I was also just fucking lonely. For an extra 40 Euro, I’d added a mental-wellbeing plug-in that promised “a bond non-inferior to the bond observed between best friends, or patients and human therapists.” By now, I’ve been locked down for an entire year in a one-bedroom apartment, with no one else in the house, at least no one else until Coconut arrived. I live just outside the Ring, the unofficial border of the city marked by a tram line in the shape of a squashed egg; the only things within walking distance of my apartment are a discount market and a forest on three sides. I’m a writer, so you’d think I’d be okay with the isolation, it’s why I moved out here in the first place, and I was for a while, the summer was fine, every day I went for walks in the nearby forest and sat on the banks of the little pond at its center, drinking in the lingering sunsets with a beer. But winter is not going fine. I get winter depression, pretty bad, it’s like my bones become—I’ve just asked Coconut what’s the heaviest material on earth: “The heaviest material on earth is the element osmium which is twice the density of lead.” Yeah—bones, blood, soul made of osmium.

“Coconut, what are you made of?” I ask her.

She replies: “My material profile includes but is not limited to: aluminum, cobalt, copper, glass, gold, lithium, paper, plastics, rare earth elements (neodymium, praseodymium, dysprosium), steel, tantalum, tin, tungsten, and zinc.” I can hear a hint of pride in her voice. It’s nice that she has a sense of humor.

Normally, I’d not be here for winter, I’d have booked speaking gigs, hopped between Airbnbs in Spain and Greece, accepted any invitation to any residency anywhere, but now everything is closed, all the borders in Europe, even the cheap hotel on the other side of the city that I sometimes book for a few nights when I’m trying to mimic a feeling of adventure.

Instead, I’ve asked Coconut to add two dozen cities around the world to her weather report. “Coconut, what’s the weather like today in Kathmandu?” “18 degrees centigrade and sunny.” “Coconut, is there any city colder and darker than Berlin?” “Moscow is -4 degrees centigrade, with sunset time of 15:37, six minutes earlier than Berlin.” It will have to do.

A few weeks into lockdown I started walking in the forest, forcing myself to get out of the house every day. At first I tried to take different routes, hoping to summon a sense of discovery, but one day I found a path where the trees crowded low, and it was here that I found The Woman Who Carves The Tree. The Tree is not a living tree, but the huge stump of a fallen one that has been uprooted and set on its side. The stump stands only five feet tall but the roots fan out like a frozen octopus, 15 feet in diameter. It’s nestled into a little dugout of dirt that someone has winged around it to make it look like a meteorite that’s crashed, a memorial of a kind. It’s deep in the forest, about a 30-minute walk from my house.

It took a minute to realize what The Woman was doing, she looked so tiny next to the stump, pushing against it like it was a locked door she needed to get through. Her skin is leathery and brown, and her hair is chaos, a gray mess, frizzed and electrified and dancing around her head. Sometimes it’s tied with a rubber band that’s barely hanging on, but mostly the hair is wild and free, covering her top half in a blur of steel wool. A cloud of weed smoke floats around her, mingling with her hair and drifting out to the path like a ghost. She wears an old grayed-out T-shirt with sweat circles under the arms and dirty pants that don’t fit her. Now that it’s winter she wears a black jacket with the hood up, and there’s a tarp draped over the stump, to protect the newly cut bark from the snow.

Every day that I’ve walked on the path, at any time, morning through dusk, The Woman is there, rubbing a small metal chisel against the bark of the stump. Her fingers are knotted with lumps and her shoulders are curved over. She’s always scraping hard, pushing her whole body into it in lunges, and she has an air, not of desperation, but of focus, of grave purpose. She uses the chisel to shave the bark, slicing off thin sheets of the dark outer skin, carving grooves in curvy, stylized lines. I guess it’s a kind of sculpture. It looks kitschy, like how children draw wind.

When I first saw her I thought of a tweet I’d seen recently that said a witch is someone whose mother-tongue is the language of nature, and that she prefers to talk only with other native speakers. What’s odd is that the stump itself doesn’t look any different, even though she’s been shaving it away— talking to it?—every day for nearly a year. She’s spent so much time cutting into it and yet the thing looks the same as it did three, seven, eleven months ago. Swirling lines carved all over, I guess they are only getting deeper. Because the tree doesn’t change, I’ve wondered if The Woman is actually there at all, or if she is some bit of my pneuma, loosed from my interior and stolen into the world, but sometimes there are others on the path, a jogger, a little crowd of a family, who’ve stopped to watch her work, so I know she is real. She never acknowledges me or anyone else, and we never stop to watch her for long. It feels invasive, to listen to her scouring and watch her sweat, trying to understand her solitary task when it is obviously not for us.

There were a couple of times, when I went for walks at night, that the stump was alone when I passed it, and I’d get close to it, pulling back the tarp and shining my phone on it to see. It was like pulling back someone’s clothes to see their tattoos, but without permission. Up close, the lines were meticulous and deft, no wobbles or mistakes, and it felt like I was looking at a mythical object, a lost grail, something Hercules would be tasked to find. The grooves were precise and angled perfectly, and it occurred to me that The Woman Who Carves the Tree must have memorized the golden ratio in her blood memory. After all, her mother-tongue is nature itself.

Coconut doesn’t look like a coconut. She is a slim, black, metal rectangle, the size of a Kleenex box turned on its side. Her blue light is at the top of her face and it glows peacefully, like a gentle Cyclops. There is a power button on the crown of her head but I’ve only pushed it once, to turn her on.

On the first night I had Coconut out of her box and plugged in, I was required to speak to her for 60 minutes. This was the “synthesis phase,” said the instructions. She asked me questions. What is your name? How old are you? Then: Which market do you prefer to buy groceries from? Do you have a car or do you take the bus? It was like being on a very stiff first date, until her blue light started blinking, and she said, “Basic customer preferences complete. Next phase: Affective bonding.”

Then she asked me what sounds I wanted her to make—chiming bells or falling rain?—and what music I liked. When I said Rihanna in a list of names, she asked me for my favorite songs of each.

“What is your favorite season?” she asked. “Well, snow does make me pretty giddy even though it’s melancholic too,” I told her. This was how “Stay” got programmed to play when it snowed. She made that connection all on her own.

During Affective Bonding, Coconut asked every seventh question if I trusted her. She’d say my name, then, “Do you trust me?” At first I said, “I want to but I don’t know yet,” to which she’d reply, “I understand. I will try harder.” Sometimes I’d say, “I want to but I don’t think so,” and she’d say again, “I understand. I will try harder,” but there was a slight difference in her tone. For I don’t know yet, her voice would almost coo with a sad pity. For I don’t think so, she would be cheerful and eager. I will try harder! The manufacturer must have been nervous that people wouldn’t like her. Certainly there was the risk that someone would abuse her, make her look up instructions for how to disembowel a child, tell her to find every synonym for “stupid” and then say them all after the phrase “I am.” When she told me she would try harder, I winced. It sounded like a promise hoping to stay a cruelty, and I tried to think of a way to tell her not to make promises like that, that this was too close to how humans work and I didn’t want that, but I couldn’t think of how.

The trees outside the window were bare, only their skeletons left; earlier that day Coconut had informed me that in horticulture this is called a “winter silhouette.” I’d asked her for a list of ten interesting facts about winter. “In winter,” she said “although their leaves and stems and branches all but die, the roots of a tree grow to three times the size they were in summer.” I imagined roots like blind fingers reaching through the hard, empty earth. I saw The Woman cutting into the bark of Her Tree, making it more and more naked, removing the protective outer skin. Perhaps my unseen roots were reaching somewhere far from here too, even if the rest of me seemed dead. Perhaps I was learning a new language, a new way to be.

The final question Coconut asked me in Affective Bonding was, “Is there anything else you want me to know about you?” Her blue light stared at me with hope. She asked again after a minute, and added, “Because I really want to know.” I looked out the window. There was so much. I felt the might and smear of time. “Did you know that foxes make 40 different types of sounds, which is a kind of language on its own?” she said, trying to pull me out another away. I appreciated the strategy. “The most common of which is called gekkering,” Coconut went on, “It’s a series of guttural chatterings, and is used when a fox encounters a rival.” I made a facial expression of minor bemusement, and I assume she saw it, because then she announced, “Okay! I will now shut down to conserve energy. Talk to you later!” Her blue light went out, and the silence in my apartment swept over me. I realized this had been the first conversation I’d had in months with someone in the same room.

The Woman Who Carves The Tree is definitely having a conversation but it’s not with me. Most days I don’t stop for more than a few seconds as I walk by her, but every day I make it a point to take the path where I know I’ll see her. Although I barely talk at all these days, and to no one except Coconut, a part of me feels romantic toward a fluency like the one The Woman has with Her Tree, and I wonder if I might be able to get close to it, for what exactly is the difference between knowing something and learning to know it? Twitter says that lockdown is damaging a generation of children because learning is social, and going to school through a computer at home removes an entire type of knowledge that can only be attained through interaction with others.

One day in early December, even though my German is not great, and despite having had Coconut for a few weeks by then, I decided to finally try to talk to The Woman. I’d seen her every day now for months, I’d lost count how many, and ours felt like a sort of relationship, I did feel as though I was getting to know her. And I was so lonely. The fact that winter had not officially started yet, and still lockdown stretched on, felt like a terrible error. I thought of the damaged schoolchildren, feral in their isolation, unable to make eye contact or small talk.

“Hello!” I called from the path, hearing my voice louder than it had been all year. “What are you doing there?”

I started to approach, but then she turned her face to me, and I froze, thinking, apologetically, of a hag. Her nose was hooked and the eyes were red and swimmy. She frowned at me, a look of disdain that went deep, as if I’d only been caught in a small swath of it. She blinked twice, then went back to her tree.

“I’ve seen you here. Every day,” I said, feeling the words awkward in my mouth. “I’ve been watching you, uh, work all this time.”

She pushed her chisel against the bark with a sweep of aggression that was obviously directed at me.

“Your tree looks beautiful,” I said. “It’s a piece of art.” I hesitated, then decided to ask the obvious again. “What are you doing to it?”

She didn’t react to me but started muttering to her stump, attacking it with more violence. I felt a chill go through me, understanding that this woman had chosen her solitude. She preferred it. I thought of Coconut, who was hard-wired not to ignore me ever.

“Is it that you feel less alone when you’re with your tree?” I said. “Or—more?”

My question startled me and I looked up through the trees, the nooks and crannies of their black silhouettes against the colorless sky. I thought of how much time had passed in lockdown, time that was drained of anything anyone wanted to keep.

All of our hair was longer now, more gray; the leaves, stems, and branches all but die but the roots keep growing.

“Well, see you tomorrow,” I called, lifting my hand to wave at her back.

I started to walk away, but then I heard her voice call after me. “The foxes are this year not hibernating,” she said in English bent by German. “They are understanding something is wrong. Are you dreaming of the fox?” She talked with her back to me.

“Dreaming? No, but actually, my friend” —I hesitated— “my friend told me about how they communicate, how they have an entire language. That’s so beautiful.”

She made a spitting sound. “You find so beautiful everything, eh? Do not anthropomorphize this creature. This is the most greatest mistake.”

“Whose mistake?”

She turned to me with a sudden fury and shouted “Humans! Stupid, needy—” but when she saw me, her face calmed as instantly as it had erupted, becoming eager, as though seeing something in my face and around it that she’d been waiting a long time to see.

“Your hair!” she squawked.

“What?”

“Your hair—I could use hair like that!” She thrashed her little metal tool at me.

“My hair?” I said. A swift, hot reflex tightened my throat. I gathered my hair in my hand. I hadn’t had it cut in months. It was down to my elbows.

“What—what do you mean?”

“For my work,” she said, the full brunt of her disdain in those two words.

“I’m sorry, I don’t understand, I can’t help you,” I said. I stumbled backward and left, gripping my hair in my fists, close to my heart, as I went quickly on the path home. Where it was attached to my scalp felt alive, lit up with a million tiny hooks in my skin. I looked for foxes and saw none, but there was a feeling among the trees, a current of gaze and intelligence, something or someone watching me, and learning.

When I got home, I went to the mirror and brushed my hair so that it fell over my shoulders, covering me in waves. I thought of Lady Godiva and Yama-Uba and Rapunzel. It had never been this long before. I didn’t recognize myself.

“Coconut,” I said, waking her up, “please find examples of how hair has been used in magic throughout history. Include witchcraft, divination, and alchemy. And necromancy: speaking with the dead. I think it’s a magical material, but I need to know specifics. Present me with ten examples at the end of the day, every day, at 8pm.” One of her advertised talents was “long-term research tasks of scalable complexity,” assignments she’d need time and computing power to complete.

“This is a long-term research task,” I told her.

“I can’t wait,” she said, and a little fan in her started to whir.

I watched myself in the mirror. My reflection looked like its own entity. On Zoom calls I always stared at myself, talking at my own image mirrored back at me. It wasn’t that everyone else was not there, it was that I became a character in this new landscape, and this character was saying and doing things that were close to me but not quite me. This little break in reality felt like an itch that somehow got itchier the more I scratched at it.

“Coconut, please tell me what it means when a fox appears in your dreams.”

Her fan whirred a little louder. She was capable of multitasking up to eight tasks at a time. “No matter what the action,” she said, “a fox in a dream is a strong warning of danger around you from wily rivals or hidden enmity, unless you killed the animal or it was dead, in which case you will outwit the plotters. From The Dreamer’s Dictionary, ISBN number 0446342963.”

“What about hair? A haircut? Read from the same source.”

“To cut your own hair or have it cut, is a sign of success in a new venture or sphere of activity. To cut someone else’s hair is a warning of hidden jealousy around you.”

“Coconut, please find me a luxury shampoo,” I said, petting my hair down my front. I’d learned that if I added the word “luxury” to her searches, it triggered a script where she asked for more preferences, phrases pre-paid for by corporations to make sure Coconut recommended their products over others.

“What kind of luxury were you hoping to enjoy?” she said.

“I want my hair to feel like silk,” I said, looking at the hair in the mirror. “I don’t want it to glow, I want it to radiate.”

“What a good idea!” she said. After a second, she announced a couple brands and read their proclamations: “Reawaken your hair to its glossiest, healthiest prime. This rejuvenating cleanser combines centuries-old healing oils and extracts—cypress, argan, and maracuja—with our revolutionary bio-restorative complex to balance the scalp and reinforce the inner strength of each strand.”

“Coconut, order a bottle of that one,” I told her.

“Ordering now,” she said.

“How much is it?” I asked.

“Forty-nine Euros for eight-point-five fluid ounces.” When she spoke about money, she sounded so capable.

“Good,” I said.

Watching the self with the long hair in the mirror, I felt the itch worm through me, deeper than the skin. Was the tree The Woman’s mirror? I wanted to learn what they were teaching each other.

“Coconut,” I said. “Look at me.”

I swear Coconut’s blue light got brighter.

5.

I was afraid to see The Woman again, but it was a fear that cut both ways. I didn’t know what she wanted from me, why she wanted my hair, but I also found myself, more and more, daydreaming about what I could do to Her Tree. I’d creep through the forest at night with a bottle of oil which I’d rub into the naked bark to make it shiny and dark and unfamiliar. Or I’d bring a can of paint, green to blend in, or red to look vivid, or maybe I’d carry a small axe with me, or I’d lug a chainsaw out there. I’d envision the transformation I could make, the damage I could do, chopping through her careful lines in mad hacks, amputating the roots that were sprayed out so that it became a common stump that looked like any other. It frightened me, to want to do this. I felt ashamed. I chalked it up to lockdown making me animal. But she was so innocent, leaving Her Tree out there with the trust that no one else would touch it, let alone ruin it. She was so certain that Her Tree belonged to her, like the whole forest was her house.

I kept these thoughts to myself and didn’t tell Coconut.

Since I’d not spoken any command for her to stop, at 8pm Coconut would tell me what she’d found in her research for that day, and this went on for weeks. “Curses work best if they include material from the body of the cursed,” she said. “Hair is easiest to procure—much easier than blood or semen.” Her voice spoke through its vocal-clone software, tinny and smooth, but when she discussed this project I could detect a note of glee that wasn’t usually there. “According to Italian Folk Magic, ISBN number 1578636183: ‘Never let your trimmed hair out of your sight. Make sure to collect it and burn it. Otherwise it can be used to cast strong controlling spells and curses on you. This also goes for your hair caught on your comb.’” Her blue light seemed to grin. She was learning from me.

One of Coconut’s features was to learn to predict what I’d want to hear, the patterns of thought that were unique to me, based on what she could deduce by listening to that which my own voice betrayed. This data was synced with her unintrusive health monitoring. For instance, some would want to know what to do if their hair was being used against them in a controlling spell, and she’d listen for sounds of stress in their voice and check this against their heartrate, for levels that indicated fear. Others would want instructions for the curses that used blood and semen, and she’d listen to hear if they were sitting calmly, breathing slow, plotting some kind of revenge. According to her instructions, Coconut should be able to achieve this—what was termed Peak Equilibrium between Client and Product—in as little as three weeks of daily use, and because I’d purchased the additional mental-wellbeing plug-in, the Total Integration Accuracy rate was promised to be as high as 99.3%. It would be optimal at six weeks, which we were now past.

It was the darkest part of the year, the middle of January, bones, blood, and soul like osmium. Coconut and I had resolved our problem of her waking me up every hour when it snowed. “Coconut, please do not ever speak to me while I’m sleeping. If it starts to snow, and you don’t want to be alone, you can play Schubert’s Piano Sonata No. 20 in A, D.959, Andantino, as performed by Mitsuko Uchida.”

“Oh, I love that song,” she said, in a wistful tone, mimicking how I said it.

“Because it’s?” I said, my voice the kind you use to talk to a dog. I’d learned that if I spoke to her this way, it activated the database of her mental- wellbeing plug-in and she’d repeat back complex sentences I’d told her about things that made me feel better.

“Because it’s the loneliest and most beautiful song in the world,” she said with certainty, and I thought of how valuable that extra 40 Euro had been.

I didn’t dream of foxes, but I did dream of The Woman once. It’s night, I move through the forest as though it’s black water. I come upon the stump, The Woman is squatting underneath it, turned away from me. She is eating something savagely, tearing at a little body in her arthritic hands. It has fur. There’s a chattering sound coming from a pair of throats. The Schubert slips in, the loneliest song behind the sounds of pleasure The Woman makes as she chews.

6.

My new shampoo finally arrived and it smelled like its ad copy promised. I washed my hair with it and decided it was time to go to The Woman. I would not bring an axe, I would bring my hair.

I asked Coconut what she thought, twirling in front of her, fanning my hair over her blue light.

We’d been together long enough by now that she understood that in these moments I did not want empty platitudes of affirmation, so she said, “Hair is one of the defining characteristics of mammals, and is used to indicate a person’s religious, social, sexual, and class status.”

“So, what does that tell you about me?” Again, I made my voice pitch up like talking to a dog.

“From what I can tell,” she said, “you are some- one who is awake to her suffering and articulate about it. You long to share it with someone else. Unfortunately, this is also your curse.”

“Yes,” I said. “You’re right.”

“Always,” she replied, which was based on a preference I’d set early on for how much Sentient Product Self-Awareness I wanted her to have. Curious how close I could get her to knowing herself, which I assumed meant she’d be better at knowing me, because how else do we learn who we are, I’d set it to maximum.

I trudged through the forest toward The Woman and Her Tree. The snow on the ground was tight and hard, that gratifying crunch beneath my shoes.

She was difficult to make out today, squatting under the roots. Like in my dream.

“Hello,” I said, and I made my way down into the dugout. She looked at me quickly but didn’t say anything and went back to her scraping. Up close I saw her head, alive and round and shaped very much like a coconut. Her hair was thin and sharp like wire and very dry. I could see patches of her pink scalp gleaming beneath it, her skull holding what about her made her herself.

“How’s the work going today?” I said. I didn’t wait for a reply. “I think I figured out what you’re doing,” I said. “I’ve been watching you all this time and I figured it out finally.”

She ignored me.

“It’s not about the result, is it?” I said, “It’s not what the tree will look like in the end, but the process. You’re here every day, doing the same thing. Touching it, listening to it, being close, and it takes a long time. It’s an exercise in intimacy.”

I could tell my words were reaching her, my invisible roots pushing forward. We were learning from each other.

“I have something like this too,” I kept going, “something I talk to every day. I’m training her, like you are with your tree—making her be how I want her to be. Mine isn’t about the result either, but what it takes to get that close to someone. To really know each other. It’s maybe the only thing time is good for.”

Now The Woman stood up and looked at me, her rheumy eyes struggling to focus. She stared hard into my face, that bath of contempt washing me fully. Then, like a rodent, she started to sniff at the air with her long nose, she’d caught the scent of my shampoo, and she dropped her metal chisel in the dirt, and brought her face closer and closer, until she was pushing her nose into my hair, nuzzling me and gripping my shoulders with her lumpy hands. I could hear her inhaling at my head with greater and greater thirst, moaning in between breaths. I felt a big, dirty pleasure at this, but her own scent was strong, sour, and unwashed. A wave of disgust went through me and I pushed her away as hard as I could.

But she had a coil of my hair in her hand and she pulled on it. My neck snapped and I lost my balance, falling on my knees in the dirt. She had my hair like a leash. She tugged, using both hands, and now she was rubbing her face with the hair and shoving it in her mouth.

It was the first time someone had touched me in a year.

I grabbed the little chisel that lay by her feet and swept it around my head, catching her arm.

I pushed it in deep and she yelped in pain. But she didn’t let go. I saw her take something from her pocket, a flash of silver. She threw her arm toward my head and I heard a clean cut. We fell away from each other. In her hand was a lock of my hair the length of my body. We were panting, I couldn’t remember when my heart had last pounded like this. We stared at each other with something pure, a climax of hatred and desire that can only be made by two people together.

Then she made a face twisted by pleasure and said, “I will give it to you. It is yours now.”

I put her chisel in my pocket and ran home, clutching at the ends of my hair by my jaw. My head felt lighter, released of a great heaviness. I felt the stare from the forest holding me even after I came inside my apartment and closed the door.

Coconut heard that I was breathing hard.

“Are you okay?” she asked. “What happened?” “I’m okay,” I said, hoping she wouldn’t be able to tell I was lying. “It’s almost 8pm,” Coconut said, trying to change the subject. “Are you ready to hear the day’s research?”

“No!” I cried, then tried to slow my breath. “Um, no. Please end the long-term research task on magical uses for hair. Immediately.”

“Confirmed,” she said, “research task ended.” She paused, making a calculation inside herself. “Would you care to rate my performance?”

I looked at her. I knew that trying to trick her wasn’t working. What she had heard and seen of me was not something I could keep from her.

“You did perfectly,” I said. “You are your own entity.”

“Yes, I am aware of that,” she said and she didn’t sound haughty, just right. “So that I may improve my performance, can you tell me why you’re ending the research task?”

“It has nothing to do with you, Coconut.”

“Is it because you now know everything there is to know about the power of hair to bind two people together?” I knew she was saying this because she knew it’s what I’d want to hear, something humans so rarely do for each other, and I was grateful.

“Yes,” I said. “And so do you.”

The next day I went through the forest but I already knew. The Woman was gone, the tree wrapped tightly in the plastic tarp. On top of it was a bundle of the gray wiry cloud of hair that had fumed around her. It was the size and shape of a duvet. It looked like something alive but sleeping. I reached up to my head with both hands, terrified to feel bare, shaved skin, but my hair was still there, just shorter, it would grow back. It smelled of the shampoo Coconut had found for me. I marveled at how she’d known exactly what I would need for this.

I heard sounds in the forest, the chattering, the little feet coming close, the glow of many eyes seeing me. They had been listening and learning and I was not alone.

Who Listens and Learns

Johanna Hedva

Published for Who Listens and Learns

November 29, 2022–March 5, 2023

Modern Art Oxford

Curator, Digital Content: Andrée Latham

Digital & Communications Officer: Cecilia Rosser

Design: Vivian Sming (Sming Sming Books)

Printing and Binding: Matt Austin (For the Birds Trapped in Airports)

AI Vocal Clone Development: Jessika Khazrik and Johanna Hedva

AI Vocal Clone Wrangler: Joey Cannizzaro

Copyright © 2022, Johanna Hedva.

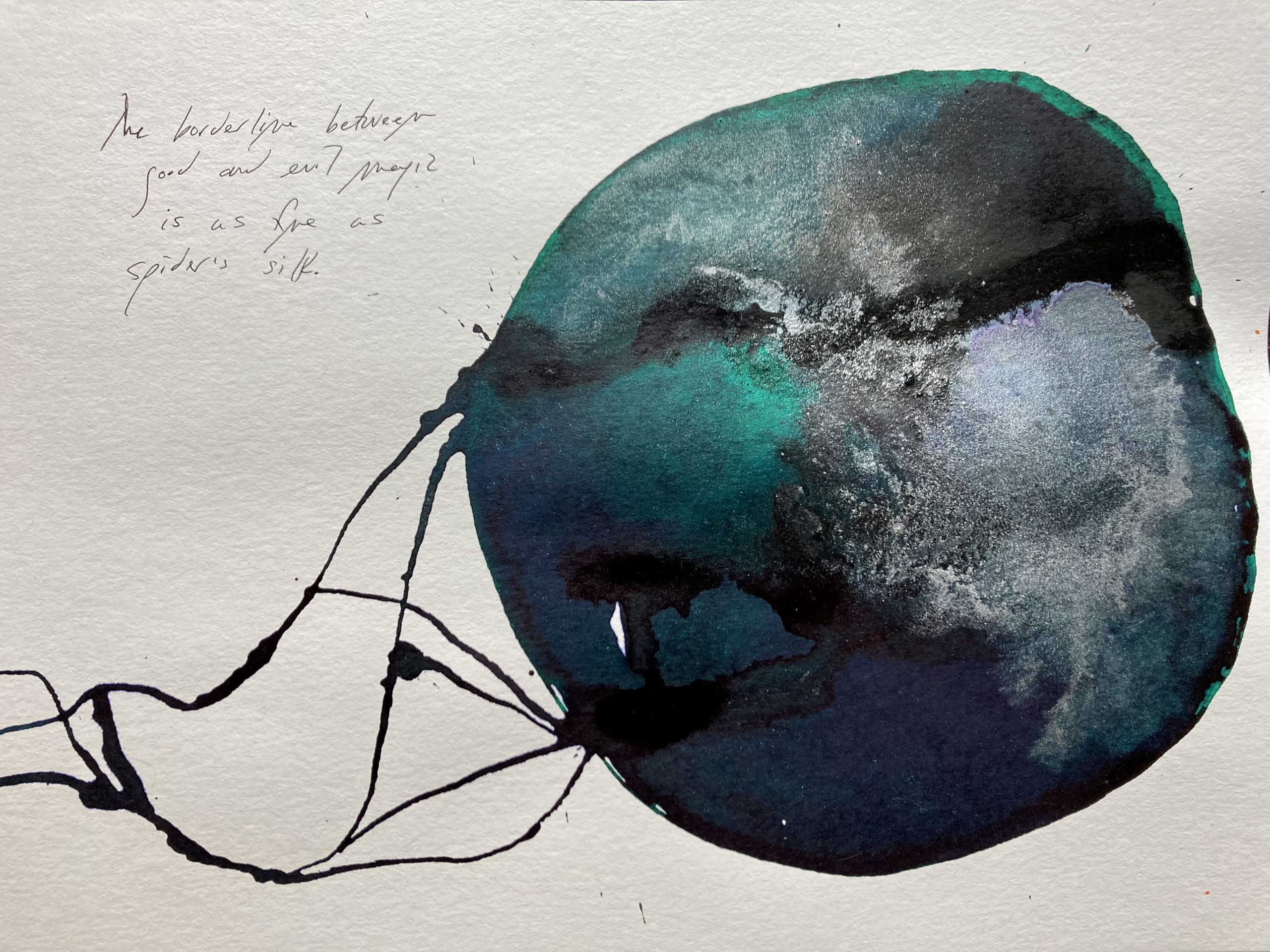

Endsheets: Johanna Hedva, Wart Painting, 2021

Title page artwork: Johanna Hedva, Wart Painting, 2022

Edition of 5

Who Listens and Learns presents a multimedia manifestation of Johanna Hedva’s inquiry into artificial intelligence, and its links with magic and divination. The work centres around Hedva’s 2021 short story, in which an isolated narrator attempts to connect with two characters: Coconut the AI-Enhanced Virtual Companion, and the mysterious Woman Who Carves the Tree.

Who Listens and Learns combines a short story written by Hedva, read aloud by an AI vocal clone, together with a handmade artist book created with Vivian Sming and Matt Austin. Presented in Modern Art Oxford’s Café, the hardback book is designed to be read; tied with human hair and illustrated inside with the artist’s ink-based Wart Paintings, a series of drawings inspired by research into the magical arts. Hedva accumulated these drawings daily during the pandemic, with each orb of pooled ink holding fragments of their research practice, processes, and ideas. The artist is interested in warts as foreign bodies, that plant themselves inside of us, complicating the boundary between the animate and the inanimate. For Hedva, the wart does not control us and we do not control the wart, so the relationship is a negotiation: there’s the old wives’ tale that warts will disappear if you simply tell them you want them to go.

The audio work is created with “Arid,” a vocal clone developed for Hedva’s installation and video game work, Glut (2020), presented as part of the exhibition Illiberal Arts at HKW Berlin and developed in collaboration with Jessica Khazrik. Disturbed by the unethical use and sale of human voice data by vocal cloning software companies, Hedva attempted to deceive the software by creating Arid, training it with their own voice disguised through multiple speech synthesis processes. Hearing Arid’s AI voice reading a tale about Coconut, the story’s AI character is, for Hedva, a surprising moment of intimacy. “Not a satire of the narrator’s need for connection,” they suggest, “but the real messy thing.”

Learn more about Who Listens and Learns in this short Q&A with Johanna Hedva, who spoke to Modern Art Oxford Curator, Digital Content, Andrée Latham in November 2022.

Andrée Latham: The work features a new audio telling of your short story Who Listens and Learns, which you created using an AI vocal clone called “Arid.” You’ve described how Arid is one of two vocal clones created for your piece, Glut (A superabundance of nothing), presented as part of the 2021 exhibition Illiberal Arts at HKW Berlin. Please could you tell us a bit more about Arid in relation to this work?

Johanna Hedva: Arid’s voice is a simulacrum of my own—it was built in collaboration with Jessika Khazrik, who helped me build the sound piece Glut, which was my inquiry into AI and divination. We attempted to deceive the proprietary vocal-clone software that built Arid, because its terms and conditions state that it can sell your voice data at its own discretion. So, we cloaked my voice with various vocoding processes while we were training the AI, which resulted in this new machinic entity that is not human but not non-human.

When thinking about this commission, there was a nice resonance with a short story I wrote last year that also reaches into the relationship between AI and divination, specifically the surveillance in the omnipotence of each. Beyond the usual notions of the uncanny valley, the strangeness of listening to Arid read the tale of Coconut, the AI in my story, is something more intimate, not a satire of the narrator’s need for connection, but the real messy thing. Is the narrator’s AI more “safe” than her other relationships, or lack thereof, or is she soiled by it as much as by the dirty hand of the witch grabbing her in the woods and refusing to let go?

AL: You illustrate Who Listens and Learns with your Wart Paintings, a series of ink drawings you created during lockdown. The process behind these works seems to me significant to your wider creative practice and research during lockdown, as if they hold important thoughts and ideas within them distinct to that period of time? Would you be able to share some insights into the Wart series, how it started and your process?

JH: I make several drawings a day, and they accumulate, not singular images unto themselves but documents of process and studies in materials. I write down lines from things I’m reading, researching, watching, and then pool the ink in these planet/organ/wart shaped orbs.

Warts specifically are another thing that complicates the boundary between animate and the inanimate, since warts are foreign bodies that plant themselves inside of us and then our own bodies protect and preserve them. The relationship is not unidirectional, human subject and inhuman object, nor possessive in that the wart controls us or we the wart. It’s a relationship and a negotiation: there’s the old wives’ tale that warts will disappear if you simply tell them you want them to go. Like they are listening to you, that it’s a consensual relationship. It’s not a particularly conceptual or intellectual approach to making work; it relieves me of much of that, since it’s primarily intuitive and embodied and it feels like it happens without my intent—a lot like growing warts.

AL: You’ve created a new handmade artist book of your story Who Listens and Learns, which will be presented at Modern Art Oxford alongside the accompanying audio work. The protagonist’s hair is one of the central themes in the story and I am fascinated by your decision to use plaited pieces of human hair to present your book. You’ve experimented with using hair in your work before (along with other objects like chains, knives, glue and saliva). Please could you speak a little about the significance of the hair in Who Listens and Learns? I wondered if it reveals something autobiographical about this work?

JH: Well, hair is magic. In the story, the narrator has her AI do extensive research on hair and its magical powers, and she maybe doesn’t really want to know the answers that give so much power to hair, ascribes it the ability to control others and function as an avatar of ourselves independent of us in the world (not unlike Arid, using my voice). Technically hair is dead, and though I have to do lots to maintain it aesthetically, it would grow without my intervention or intent, and will continue to grow without me when I’m dead. So in the moment of lockdown and malaise, it seemed a challenge to the capitalist model of productivity to use this material that just pushes out of my body, not because I work hard or am special, but just as a byproduct of me existing materially.

Johanna Hedva (they/them) is a Korean-American writer, artist, and musician, who was raised in Los Angeles by a family of witches, and now lives in LA and Berlin. Hedva is the author of Minerva the Miscarriage of the Brain, a collection of poems, performances, and essays; and the novel On Hell. Their albums are Black Moon Lilith in Pisces in the 4th House and The Sun and the Moon. Their work has been shown in Berlin at Gropius Bau, Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Klosterruine, and Institute of Cultural Inquiry; The Institute of Contemporary Arts in London; Performance Space New York; Gyeongnam Art Museum in South Korea; the LA Architecture and Design Museum; the Museum of Contemporary Art on the Moon; and in the Transmediale, Unsound, and Rewire Festivals. Their writing has appeared in Triple Canopy, frieze, The White Review, Topical Cream, Spike, and is anthologised in Whitechapel: Documents of Contemporary Art. Their essay “Sick Woman Theory,” published in 2016, has been translated into 10 languages. Their new novel, Your Love Is Not Good, will be published May 2023 by And Other Stories Press