Monica Sjöö: Reflections from the Young Creatives Collective

During their time with the Young Creatives Collective, Alina, Arina, Isabel, and Mia worked on a series of reflections, exploring their own interpretation of Monica Sjöö’s work, currently on display as part of Monica Sjöö: The Great Cosmic Mother (18 November 2023 – 25 February 2024). Below, they share their personal responses to individual works, and reflect upon their relevance.

Monica Sjöö Sheela na Gig, Creation (1978)

Alina Hu

Sheela na Gig, Creation (1978) captured my attention with its visceral imagery. Not in a negative or aggressive manner. It simply elicits a kind of respectful acknowledgment of the Goddess’s work of creation. There is immense beauty in the gentle grasp of her vulva and the bright red which flows forth, providing energy to the depictions of life while also signalling menstrual bleeding. Her being dissolves into earth itself; a reminder of the eternal protection offered through deities such as the Great Mother, Mother Earth, or Sky Mother – all female figures recurring across many world cultures who create and protect life.

This almost universal belief is echoed in the title of Sheela na Gig, Creation. Sheela na gigs are architectural decorations of naked female figures with exposed vulvas placed above doors and windows to ward off evil spirits. The raw portrayal of female anatomy is now the subject of controversy in the media, yet it has historically been seen as a sort of portal leading to a divine power, where life is created.

Beckoning back to that former feminine glory, there is nothing grotesque about this work. It’s raw in the most humane sense, and I think that’s beautiful.

Our Bodies Ourselves (1974)

Arina Colun

Monica Sjöö’s work, Our Bodies Ourselves (1974), invites me to reconsider my understanding of women in society, especially during my university years – a time of ongoing self-discovery. This encourages me to question the established narratives.

As I immerse myself in Sjöö’s work, I can’t help but draw parallels between the demands of the Women’s Liberation Movement of the 1970s and my own journey of self-identification. Her painting underscores the idea that our bodies serve as symbols of identity and autonomy. This insight mirrors my current personal odyssey during university, especially when I am considering my future career path.

Sjöö’s work remains strikingly relevant today, emphasising the importance of embracing diversity and acknowledging the distinct journeys of all women. For me, it serves as a poignant reminder of the need for introspection and the courage to challenge societal expectations, not only in terms of personal identity but also in the pursuit of a fulfilling life shaped by my own passions and convictions.

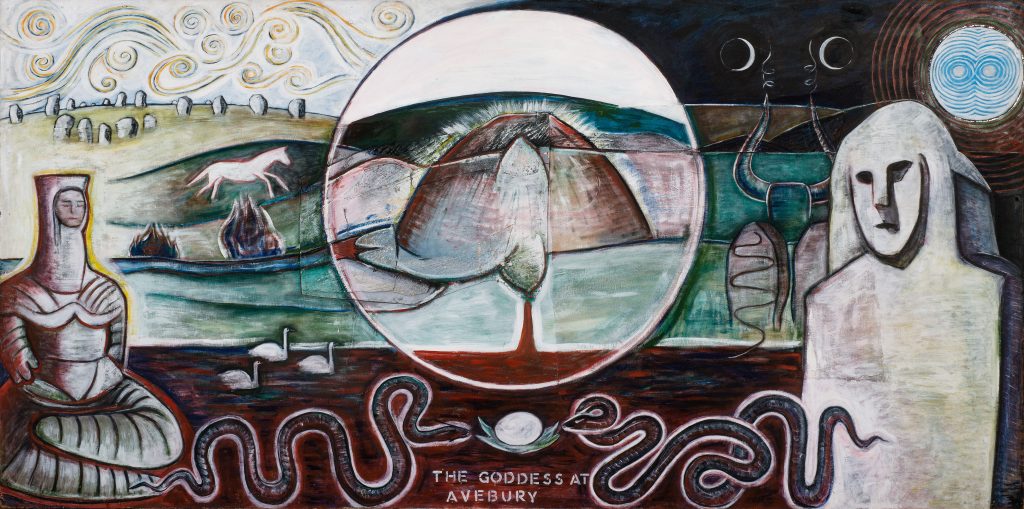

The Goddess at Avebury and Silbury (1978)

Isabel Elsner

The snake symbol in Sjöö’s work encompasses several themes. Within the primarily Christian western context, snakes represent evil and provide validation for the misogyny of Abrahamic religions, in which women are viewed as susceptible to temptation. But Sjöö subverts this by celebrating Eve’s role in biblical history as mother of humankind. Mantras on Sjöö’s feminist campaign posters include phrases such as ‘she the serpent power…she the mother of all’, showing how Sjöö focuses on the strength of womanhood, not its negative stereotypes.

In The Goddess at Avebury and Silbury (1978), Sjöö paints snakes swimming through blood, evoking menstruation and thereby reclaiming this symbol further within the feminine sphere. She rejects patriarchal religion, moving towards the freer spirituality of pagan movements, where snake deities – as well as women – play a more positive role. Aboriginal Australian mythology, for instance, reveres women for possessing the same life-giving power as their creator god, the rainbow snake.

Sjöö’s use of snake imagery could be considered cultural appropriation, as she takes sacred iconography out of its original context for the sake of her feminist manifesto. But like a snake shedding its skin, this imagery is also perpetually evolving. Sjöö doesn’t blithely repurpose motifs from other cultures – she contributes meaning to these ancient symbols, in a progressive and empowering way.

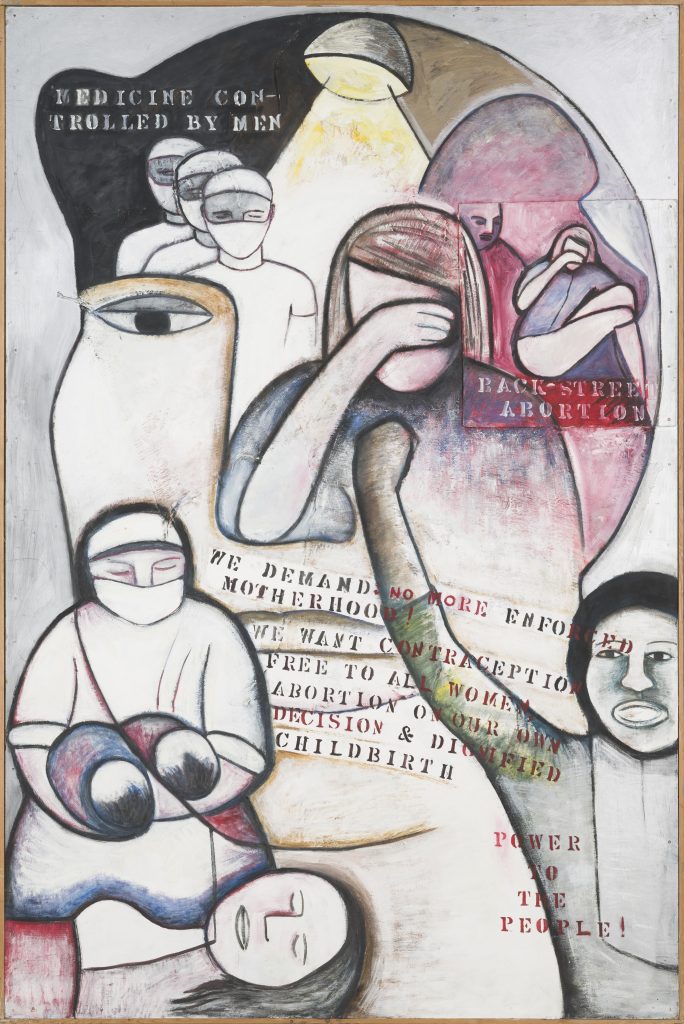

Back Street Abortion – Women Seeking Freedom from Oppression (1968)

Mia Annesen-Wood

In this painting I see myself, and generations that have passed. Access to abortion is a concern for all, transgender and non-binary people as well as cisgender women. With the overruling of Roe v. Wade last year in the U.S. Supreme Court, this issue is unfortunately ever present.

Sjöö’s stylistic choice of figures in Back Street Abortion – Women Seeking Freedom from Oppression (1968) reflects the diverse range of people in need of life saving medical care. Capitalised text reflects the anger felt by myself and others, yet the diminutive size of the lettering feels like it has little impact. Our shouts are not loud enough to those in power. It has been 55 years since Sjöö produced this work and 66 years since the Abortion Act of 1967 came into effect in Britain.

As a young person, I feel profoundly uplifted by this work in the sense that I can connect to other generations who have fought this struggle whilst also being deeply saddened by its relevance today.

Find the Young Creatives’ reflections on Monica Sjöö’s works displayed in the galleries when you visit.