A Seat at the Table - Zola Tatton

During the opening week of Boundary Encounters, a group of young artists, aged 16-18, joined commissioned artist Harold Offeh for a week of collaborative design and creative experimentation in the gallery. The young artists were tasked with creating pieces of furniture for Harold Offeh’s Pavilion. Here, Zola Tatton tells us about her experience.

Can you describe the inspiration behind the project and the chair you made?

Harold Offeh explained that the aim of the chairs was to create a space for the public which expresses the theme: ‘a seat at the table.’ To me a seat at the table doesn’t just mean who gets the opportunity to influence others and have access to power but how you can express yourself when you are in these formal settings. Often it is frowned upon to show emotion or vulnerability even when these feelings are incredibly important in creating change and progress. People who do show these things openly are usually either dismissed as weaker or seen as disorganised.

In a similar way, those who speak about the past and their previous experiences are also often seen as unprofessional, especially when they are discussing marginalisation and the complex and unjust history of power. As a result people who talk about the past or their emotions are considered difficult to work with or messy. However I wanted to take this idea and twist it. I made a chair that openly displays this messiness and becomes a space where people feel comfortable being messy and complicated.

Why did you choose these materials, colours, and shapes to work with?

I wanted the materials I used to show their history. I found wood with small fragments of William Morris wallpaper left on it that was from the 2014 ‘Love is Enough’ exhibition by Jeremy Deller. There were also pen marks and measurements, drill holes and a few dents that further showed the history that well used materials have. I love how the materials collected and recycled in the modern art oxford workshop become an extension of the gallery’s archives that are also part of the exhibition, which tells a larger story about art within the city.

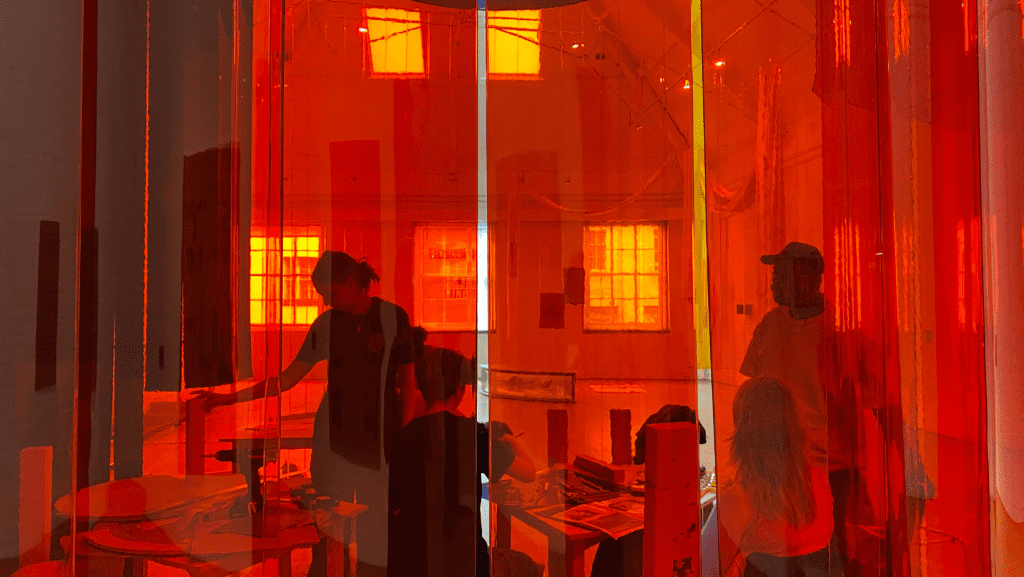

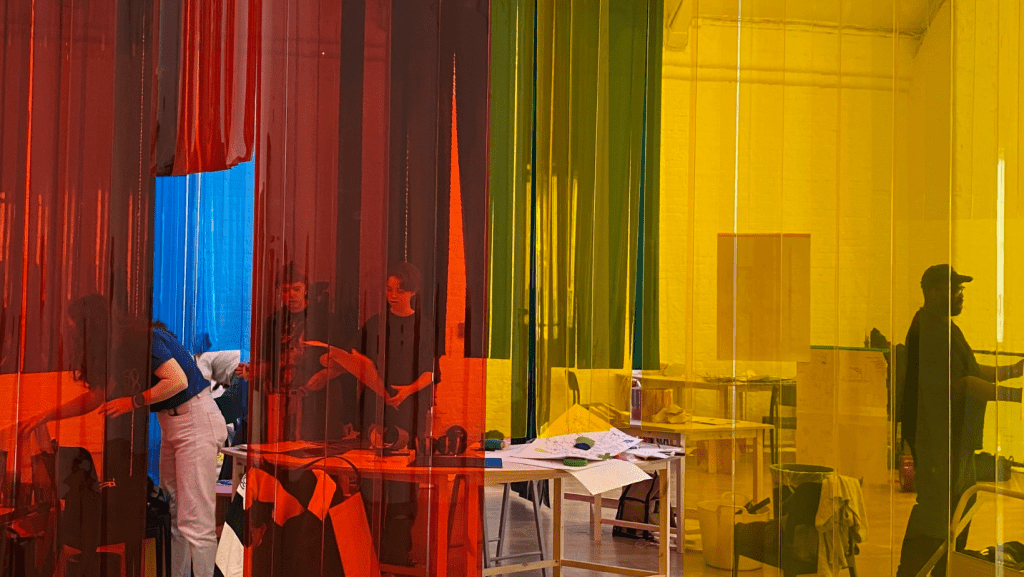

Outside the basic structure of the chair I added strips of plastic that I had cut into more organic looking shapes that match the jagged shapes of the wallpaper fragment. They were recycled, originally being offcuts from the overhead pavilion structure that I draped across the chair haphazardly so they tangled and twisted together. Overall the chair looks a little strange and confused with all its contrasting elements and clearly reused materials. However, I hope this unusual messy chair helps people celebrate their own complexities in a more open way, and accept the same messiness in other people.

Can you sum up your experience?

I felt that in the course of the project the gallery’s space felt more and more open to messiness and imperfection. It was filled with the sounds of sawing and drilling, people carrying equipment around and piles of sawdust: things that would normally be kept behind the scenes. This public display of messiness, to me at least, was freeing. The gallery became an open and honest space that was approachable, welcoming many different ways of exploring art and community.