A Look Closer: Hidden References in Belkis Ayón's work

Throughout Sikán Illuminations, Belkis Ayón often references well known scenes and imagery from art history. Here we begin to unpick these allusions to take a closer look into Ayón’s captivating world.

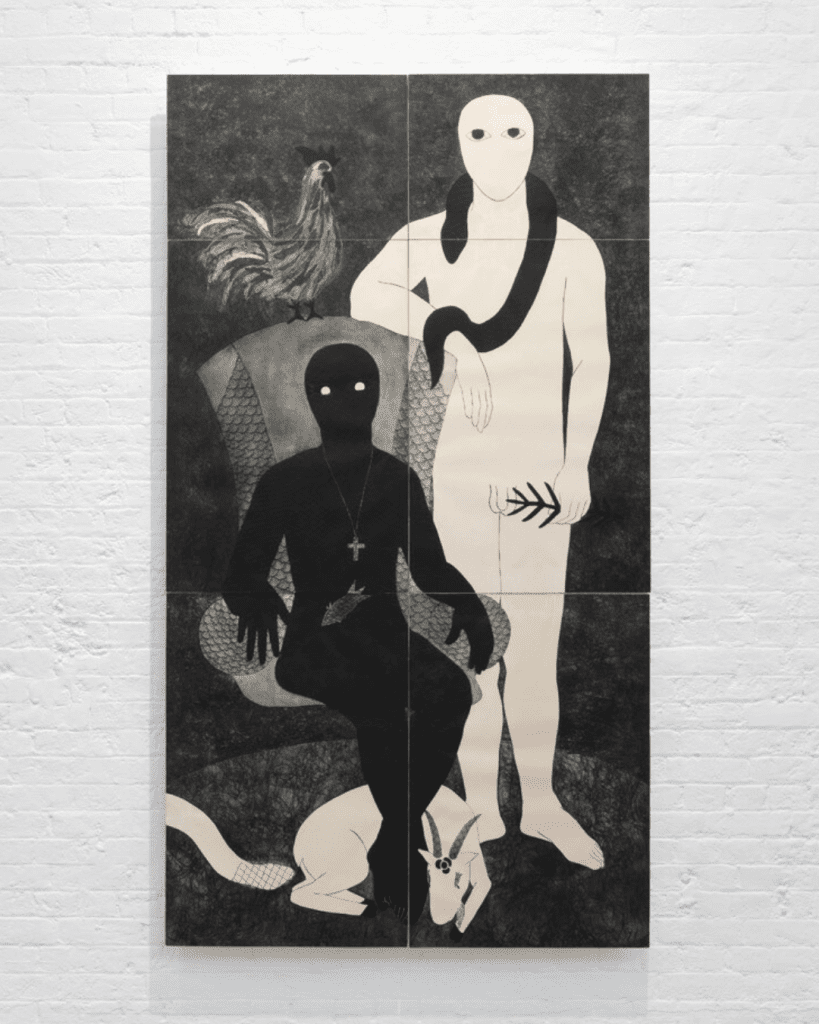

First up, let’s take a look at La Familia, 1999.

At first glance, the image depicts Princess Sikán seated on a chair, with Mbori- the goat sacrificed alongside her in the Abakuá myth- curled at her feet. The way the goat wraps around her suggests a symbolic unity between them. Besides her stands a paternal figure. Ayón creates a traditional portrait composition to signify the power balance and strength of the figures.

The triangular arrangement of the figures recalls classic depictions of the Holy Family in Christian art. However, Ayón subverts this familiar composition by weaving in Afro-Cuban iconography, firmly establishing Sikán and her father as central to the spiritual framework of the Abakuá religion.

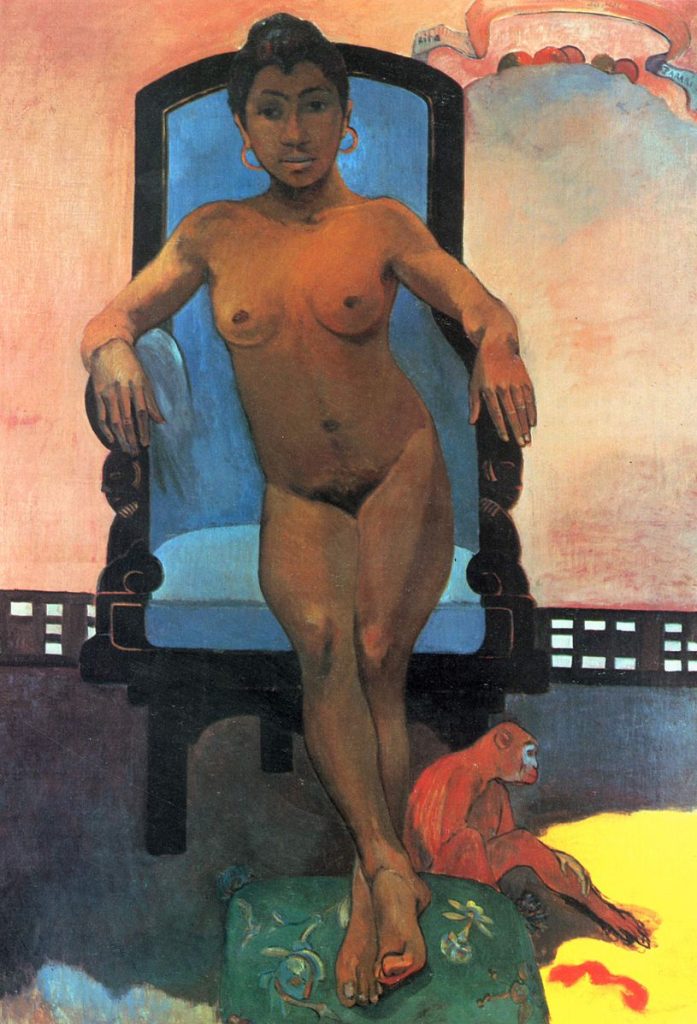

As we look closer, we see Ayón’s work echoes Gauguin’s portraits, particularly his Portrait of Annah the Javanese (1894). Having attended art school in Havana, Ayón particularly admired the work of the French painter Paul Gauguin (1848-1903).

In Gauguin’s painting, Annah sits awkwardly on a chair, naked, her pose shaped by the male artist’s gaze. Her defiant expression suggests agency, but the power dynamics of the scene – her role as subject to Gauguin’s portrayal-reflect the colonial and objectifying lens through which she was viewed. Modern critics have called out the exploitative aspects of Gauguin’s work, especially his depictions of non-European women.

In La Familia, Ayón draws parallels between Sikán and Annah through the similar seated pose. Is she challenging Gaughain’s objectifying gaze? Is she portraying Sikán as dignified? As spiritual? As vulnerable?

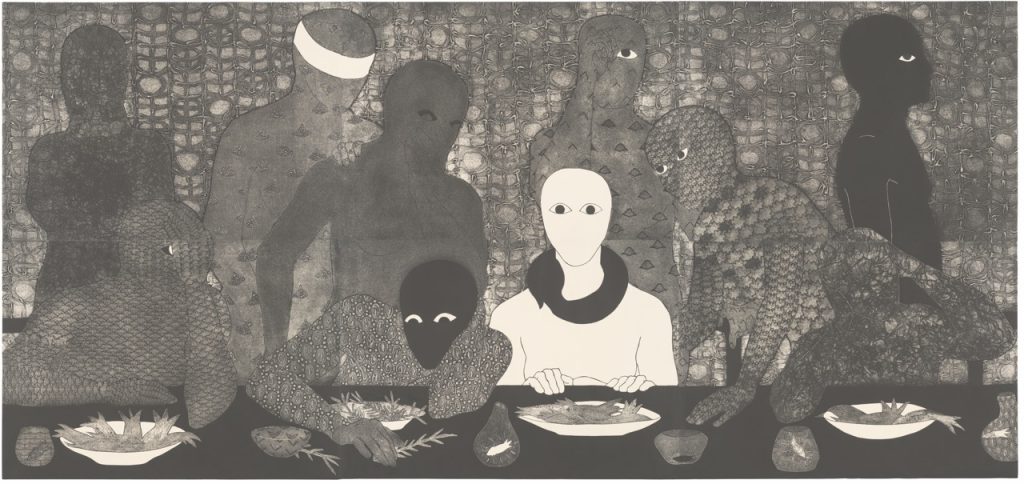

Next up, La Cena (The Supper) 1991.

La Cena is Ayón’s first large-scale collograph depicting an Abakuá ritual. The scene features nine women and one man, the Leopard Man – a symbol of patriarchal power – who has broken tradition by consuming the sacred fish, Tanze. The women, gathered for a ceremony, appear surprised and unsettled.

The composition and title evoke The Last Supper, Leonardo da Vinci’s iconic mural, which captures the moment after Jesus reveals one disciple will betray him. In The Last Supper, emotions of anger, shock, and disbelief ripple through the gathering. In La Cena, Ayón replaces Jesus with Sikán, who gazes out at the viewer with wide, captivating eyes. By connecting the two works and placing Sikán in the role of the savior, Ayón elevates her as a central figure in Abakuá mythology.

This parallel also invites a rethinking of traditional narratives: where The Last Supper emphasises betrayal and redemption within a patriarchal framework, La Cena challenges that structure by centering Sikán, a female figure whose fate is entwined with themes of transgression, sacrifice, and power. Ayón’s reinterpretation transforms the ritualistic meal into a poignant critique of gender, authority, and societal expectations.

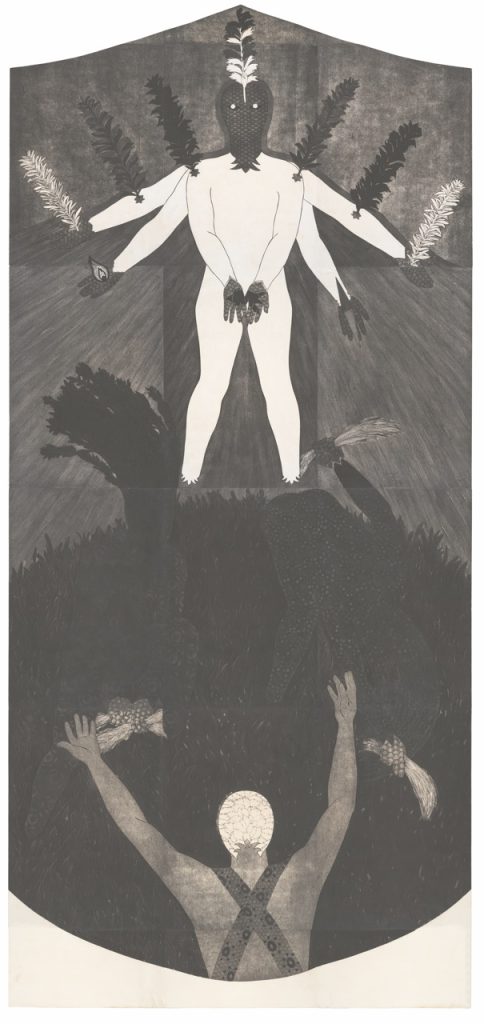

Finally, let’s consider Belkis Ayón’s largest work, Pa’que me quieras por siempre (To Make You Love Me Forever), 1991.

In this piece, Ayón draws upon the Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian, a subject famously depicted by artists such as El Greco, Botticelli, and Botticini, among others. Saint Sebastian is often portrayed as a symbol of resilience and transcendence. By referencing this iconic motif, Sikán is cast as a martyr. In Abakuá mythology, Sikán was killed for discovering the sacred voice, a secret forbidden to women. Through this connection, Ayón aligns Sikán with the universal archetype of the martyr, highlighting the magnitude of her sacrifice.

After her death, Sikán gains power and earns the respect of the Abakuá brotherhood, underscoring the title To Make You Love Me Forever. The comparison to Saint Sebastian highlights both the endurance of her sacrifice and the patriarchal structures that demanded it. The work serves as a poignant tribute to Sikán’s resilience while powerfully critiquing the societal forces that sought to silence her, reflecting Ayón’s broader exploration of power, gender, and sacrifice.