On World Elephant Day, we take a closer look at the huge elephants in Samson Kambalu’s exhibition New Liberia, and the symbolism of the elephant mask in Malawian Nyau tradition.

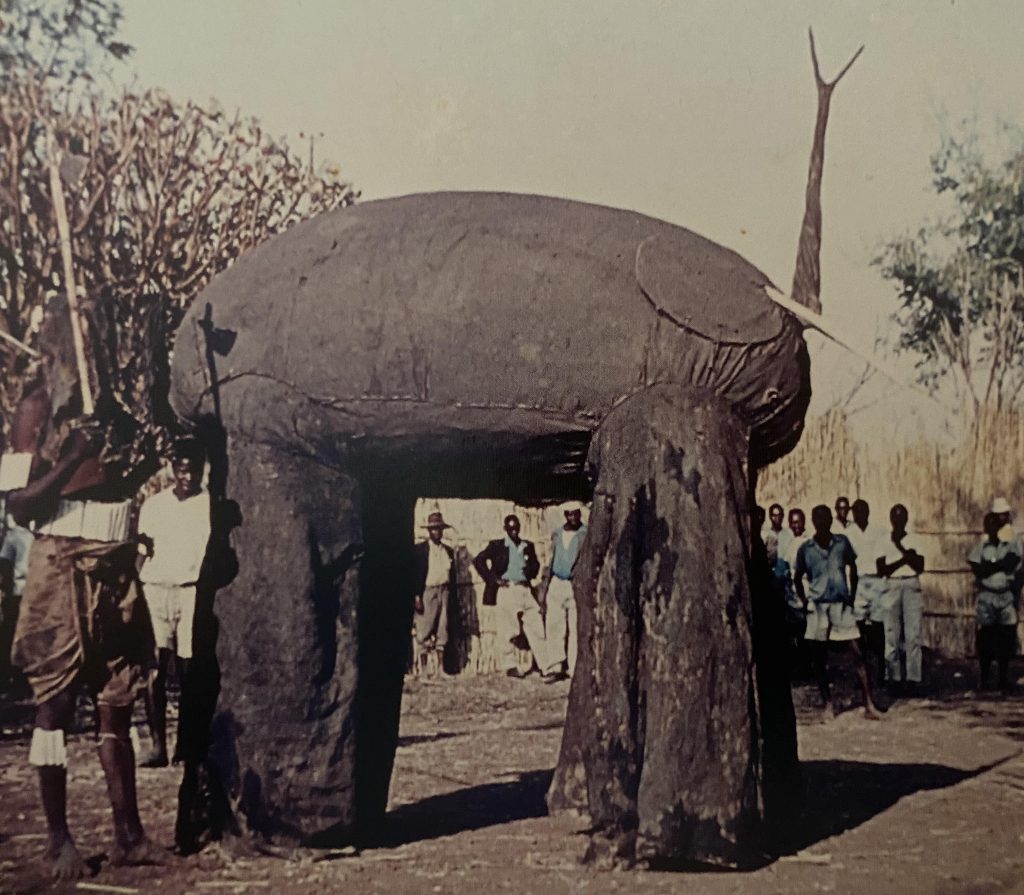

As you enter Samson Kambalu’s exhibition New Liberia, you are greeted by two Nyau elephant chiefs. Nyau is the secret society of the Chewa people that populate Malawi.

Kambalu’s work is informed by his interpretation of Nyau. The Nyau perform short energetic dances for the traditional Gule Wamkulu (The Great Dance) to communicate ancestral wisdom* and generate harmony in moments of transition. For these dances they wear ‘masks’, costumes assembled from cut-up materials.

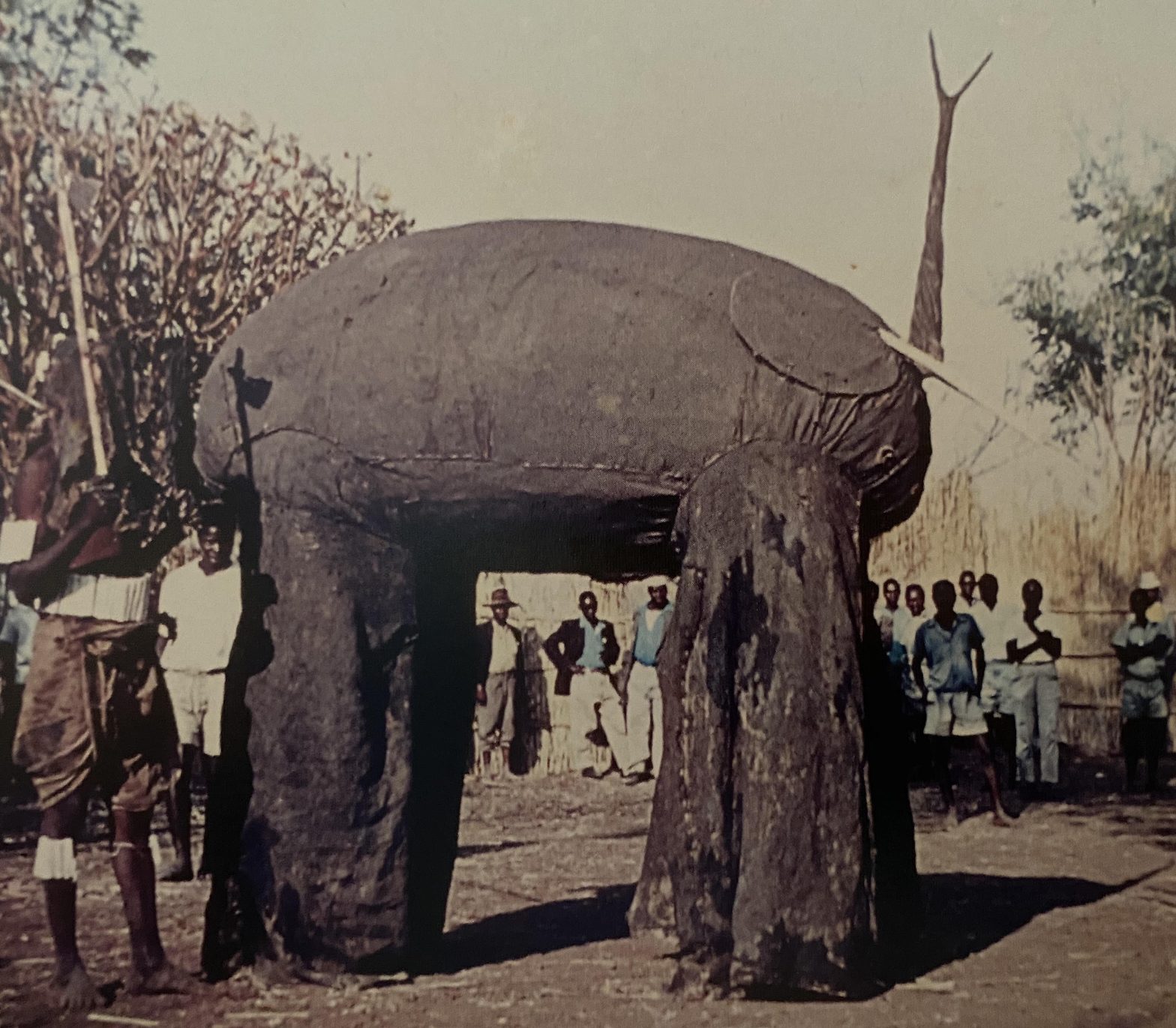

Here you can see an elephant (called Njovu in Chewa) mask at a ceremony in Lilongwe, Malawi in the 1960s. Each of the elephant’s legs is wide enough for one dancer, and this is how the four dancers animate the mask through the dance.

The Nyau have many masks representing different characters and animals, but after Kasiya Maliro (the Great Mother antelope), the Njovu (elephant) is the most important structure of the ceremony, representing the father ancestor and chief.

Traditionally, the elephant performs for initiation ceremonies, enthronements, funerals and commemoration rights of chiefs and other dignitaries. The elephant is a symbol of fertility and so they are present during puberty rites. Only senior people who have been through the highest degree of initiation are allowed to construct the elephant mask – the structure is kept well away from junior initiates.

To make the masks, a bamboo frame would traditionally be thatched with grass and then smeared with clay. In more recent years, canvas might also used to cover the frame. The elephant’s long straight tusks, flexible nose, ears and mouth are then added, as well as a short mobile tail on the back.

Kambalu’s elephants descend from and also continue the Nyau masking tradition. As Kambalu imagines a future utopia of social justice called ‘New Liberia’, these elephant masks become a meeting point of past and present, and welcome visitors to the initiation ceremony for this new place, or way of living. Passing down ancestral knowledge, they also propose the possibility of new futures.

Their wooden structures covered in cut up Oxford University gowns, the Drawing Elephants (as Kambalu has called them) bring together spiritual and academic community rituals. To create the elephants, the university gowns were disassembled, and then reassembled in their new guise as mask.

This process of deconstructing and reimagining becomes a powerful symbol of the need for fundamental rethinking and reordering in order to achieve meaningful social change. Kambalu also draws on the social philosophical insights of John Ruskin (1819–1900), emphasising the importance of both art and education as ways to see the world afresh.

Curious to know more about how Kambalu’s elephants were made? Click here to meet to the elephant-building team and watch them coming to life in the gallery.

Click here to visit Samson Kambalu’s exhibition New Liberia.

* Kambalu explains that the term ‘ancestral’ wisdom is a European simplification. During the Gule Wamkulu dance, initiated Nyau primarily bring energy from the ‘pre-ontological void’, the space between life and death. The understanding is that there is not a clear distinction between the living and the dead, and, represented in the ceremony, the spirits are physically present.

The first image comes from: Claude Boucher, When Animals Sing and Spirits Dance: Gule Wamkulu: the Great Dance of the Chewa People of Malawi, 2012 (Mkatakata: Kungoni Centre of Culture & Art)