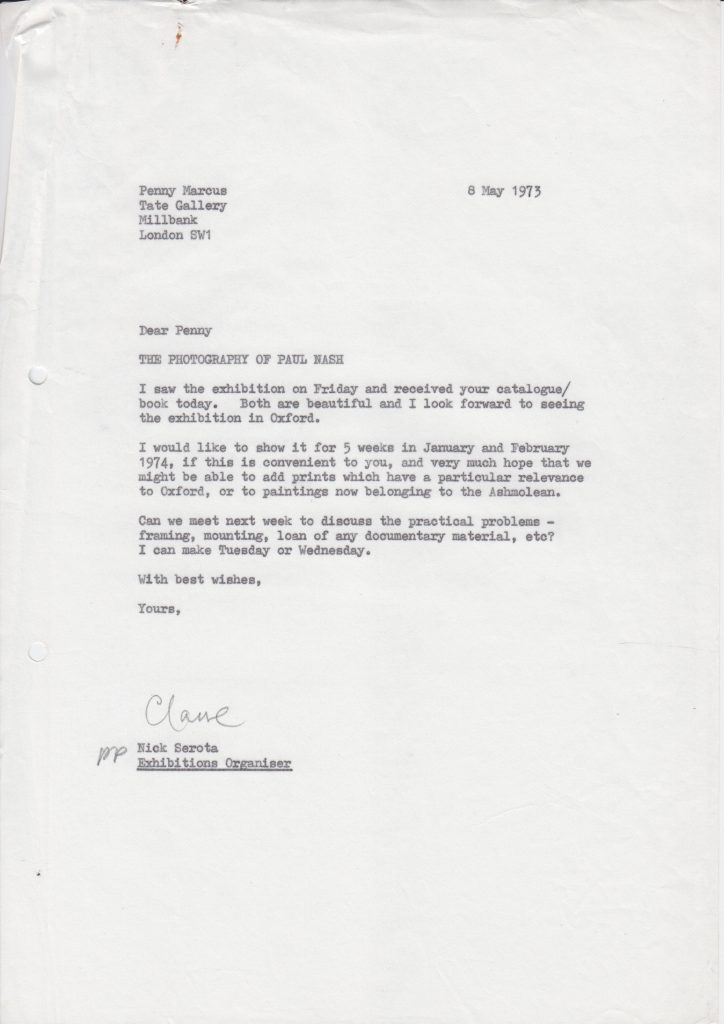

One of the early shows during Nick Serota’s tenure as Director of the then Museum of Modern Art Oxford in 1974 was an exhibition of photographs and a small selection of accompanying watercolours by the British painter, Paul Nash. An exhibition of Nash’s photographs had been shown at Tate Gallery in London the previous summer, prompting Serota to bring them to audiences in Oxford, since some of the photographs were of local landscapes taken by Nash following his move to Boar’s Hill in Oxfordshire after the outbreak of the war.

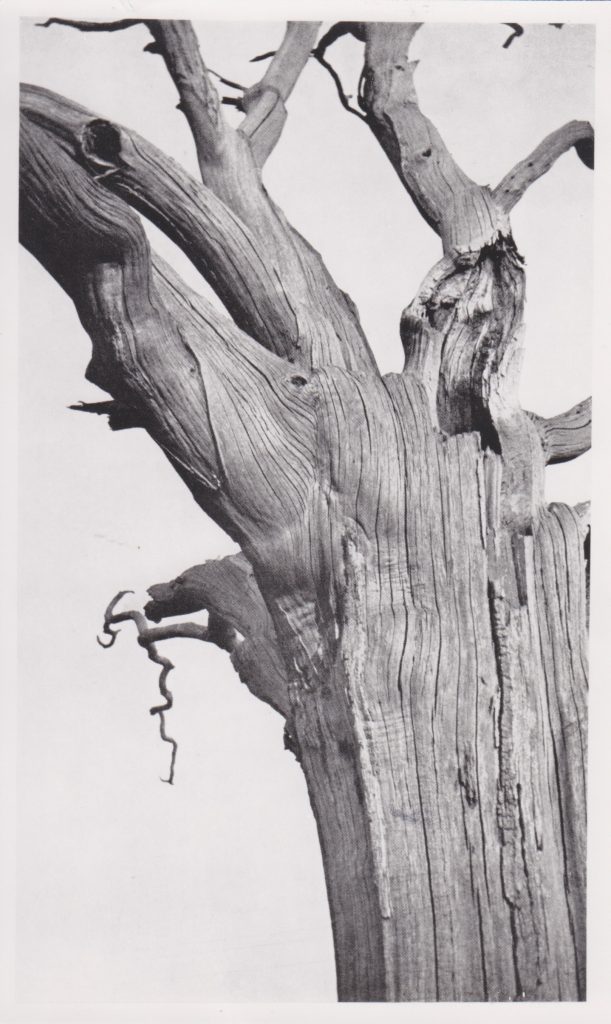

The exhibition notes for the show, held in our archive, explain that Nash had taken photographs since the 1930s when his wife gave him a No 1A Box Kodak Series 2 camera – the only camera he ever owned – using it consistently until his death in 1946. He used the photographs as research and source material for his paintings from the mid-1930s onwards and became increasingly reliant upon them later in his life when his asthma prevented him from working outdoors.

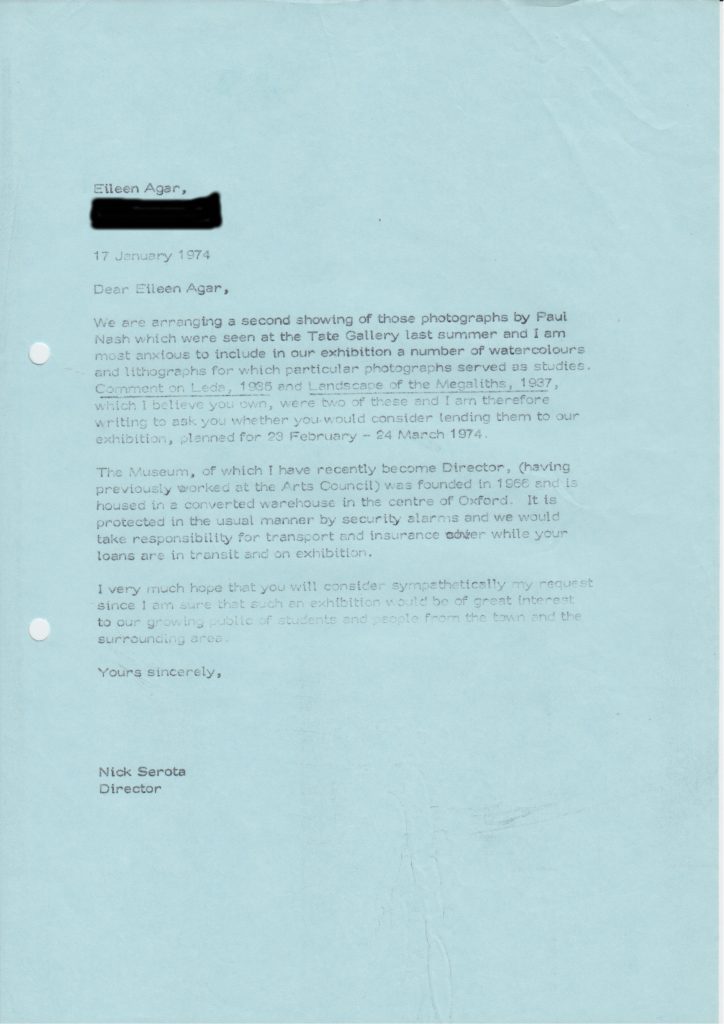

A faded and fragile typed letter dated 17 January 1974 from our archive is a polite fragment of correspondence between Serota and the late surrealist artist Eileen Agar, requesting two works in her private collection for inclusion in the show. Agar met Nash in Swanage in Dorset in the mid-1930s where they began an intense relationship that also led to artistic collaboration. Nash played an important role in her career, recommending Agar to Roland Penrose and Herbert Read who were at that time organising the 1936 International Surrealist Exhibition at the New Burlington Galleries in London. She became the only British women to have work included in that seminal exhibition, which launched her international career.

These archival materials, and their proximity to artists and their lives, never ceases to attest to the importance of these unique records and offers a powerful charge to those of us who have the privilege of handling them as we mark our 50th anniversary.

I chose this exhibition because I wished to highlight that photography has been a consistent strand of our programming since the foundation of the gallery, long before it was recognised by public institutions as of equal status to fine practices like painting and sculpture.