Common Ground reflects on the themes of Sam Skinner’s film, created as part of Situated Ecologies. Explaining the history of the Enclosure Acts, the radical power of common green space, and the ongoing fight to save it, this blog examines how an artistic practice can be rooted in green space.

Enclosure

Between 1604 and 1914, 6.8 million acres of common land in the UK were enclosed through the passing of over 5,200 Enclosure Acts and Awards. One of these is the Cowley Enclosure Award of 1853 that includes the area of what would become Florence Park in East Oxford, which was the focus of my film commission for Modern Art Oxford’s Situated Ecologies programme.

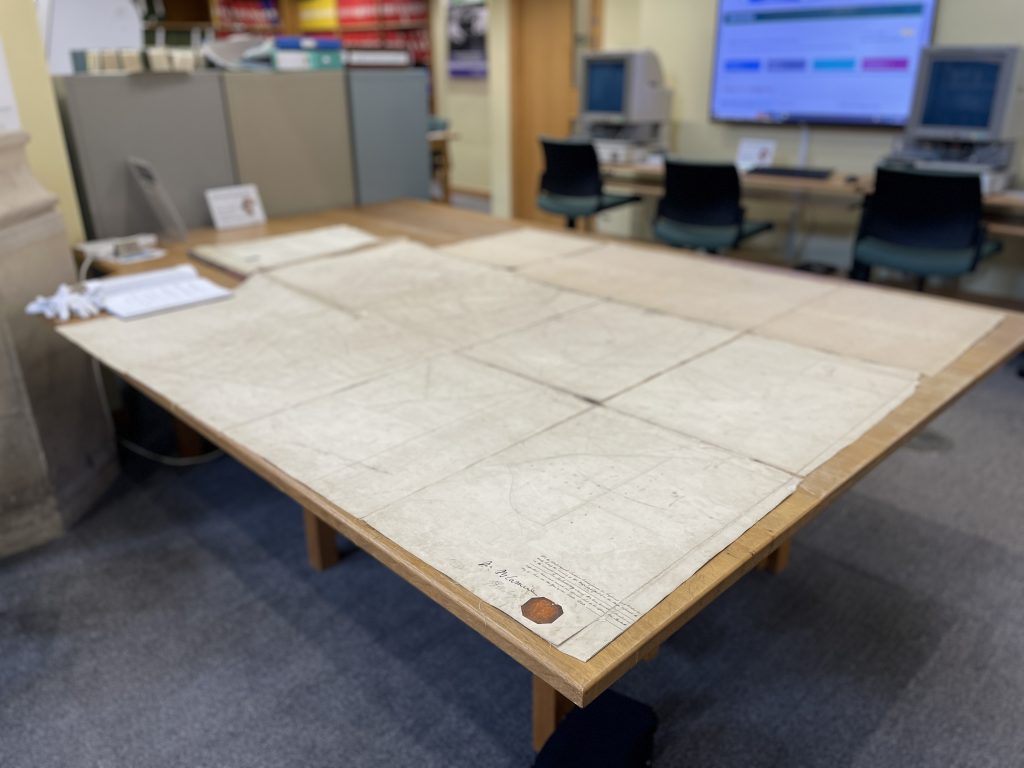

The Enclosure Award, held in the collection of the Oxfordshire History Centre, takes the form of huge map and ledger marked with seals shown here. It details the removal of commoning rights and the redistribution of land in Cowley to individual owners. Some of these areas were later developed into what became allotments to support those adversely affected by enclosure, including Elder Stubbs Allotments which features in my film.

I want to draw attention to this history, and the seals found on the Enclosure Award, which I have digitally cut from their legislative substrate, to foreground how greenspace and our ability to access it is made, and continually remade. The archetypal vermillion of the seals and the unicorn and lion propping up the royal coat of arms stamped upon them speak of the power and authority to make law and to

enact. Yet, the seals’ cracks and fragmentation suggest a fragility and mutability to this power, to the matter upon which it imprints, which extends to the dividing lines of the map and the land itself.

The Grass Was Taller Than Me focuses in on greenspaces that have in many ways grown out of the cracks of enclosure. My own Fig Studio project itself grew out of these cracks too – an overgrown corner of Elder Stubbs Allotment and within this blog entry I want to attempt to introduce and situate Fig Studio and some of the projects I have been involved with, which will I hope in turn situate the film.

*

Fig Studio

To situate is to consider, work with, or to place something, including one’s self, in a particular location or context. Everywhere and everyone is different, but shares things and is entangled together, to one degree or another. Thus, to work in a situated way is to affirm difference and diversity, but also kinship and commonality.

My work with Fig Studio is guided by this sense of place, of sensing place, with an emphasis on art as a social practice, which tries to think/make through/with the ethical and ecological implications of climate change and biodiversity loss. To date, Fig projects, have generally: occurred outside; used biodegradable materials; involved plants; considered the role of greenspace in urban environments, in

particular parks and allotments; and connected to broader contexts such as the industrialised food system and land justice.

I use ‘fig’ in the sense of the plant, (inspired by a fig tree on my allotment), but also for the association with ‘fig.’, short for figure, image, or diagram, to link the natural with the cultural. Although, I nominally lead the project, I like to think I work for the fig tree, and projects momentarily gather under its variously real or imaginary canopy. The epithet ‘studio’ emphasises that this a project concerned with materials, materiality, and materialising; acts of making, assembly, hosting, and collaboration, with different people, plants, community groups, and ecologies, whilst also seeking to affirm the value of studio culture, studio time, and process itself.

I began Fig with an offer to artists to develop something on a 100m 2 patch of earth on Elder Stubbs Allotments. I would support the development of their work as a curator, artist, and amateur horticulturalist/grower, helping with propagation, planting, weeding, watering, and the like. Instead of a so-called ‘white cube’ I was

offering a fertile green and brown square. While this didn’t make sense for many artists, it resonated with Oxford-based creative JC Niala:

“I have an idea,” she said, “Could we recreate a 1918 style allotment?” JC wanted to explore connections between the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918-19 and the Coronavirus pandemic, in particular the role of outdoor space and allotments within them. We grew heritage

varieties, followed guidance from TW Sander’s 1918 book Allotments & Kitchen Gardens, and JC used the space as a living archive and studio to research and write within. We hosted workshops and poetry readings, with JC and others reading amongst the beans and the cabbages, food was shared, and a book was produced. An exhibition and event was hosted at the Old Fire Station with JC and writers including Claire Ratinon, and there was an online exhibition at the Museum of English Rural Life. JC was awarded the Public History Prize from the Social History Society for the project and our produce from the 1918 Allotment won Best in Show at the Elder Stubbs Festival! I list these various processes and outcomes to underline

how art can situate itself and thrive within different ecologies, different homes, but also how more traditional arts spaces, such as the gallery, the theatre, and the book, can be important places for such projects to land, grow, and cross-fertilise.

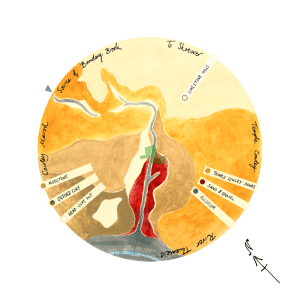

Other Fig projects have included, Nor Greenhalgh’s Elder Vernacular, which developed a synchronous process of mapping and digging into the geography of East Oxford. Nor used local materials, variously dug-up or grown on or near the Fig allotment, within the making of the maps themselves. She also created an artist’s toolbox from these materials shared and used via a programme of workshops with

community members of mental health charity Restore based at Elder Stubbs Allotments and a book was produced of the project.

The Greenspace & Us project explored barriers and enablers to how young women and girls access greenspace. The project was led by youth workers from Name It youth scheme and researchers from Oxfordshire Council and the University of Oxford, who set up a new youth group of young women and girls interested in greenspace. Fig commissioned Resolve Collective to work with the group to co-design an intervention in Marsh Park, which resulted in a shelter and picnic bench and accompanying publication and manifesto produced with Common Books. A report and journal paper has also been produced sharing the research and the youth group have continued to meet and develop projects.

Most recently I worked again with Julia Utreras from Common Books and JC Niala on a project in collaboration with Greenpeace entitled The Waiting List. Using Freedom of Information requests to all principal councils in the UK we discovered that the number of people on allotment waiting lists nationally was 174,183. This data was mobilised in tandem with the 1908 Allotment Act, which states that if 6 or more people from different households demand an allotment the local government is duty bound to act. We made a giant seedpaper banner that was presented at the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities to make a demand for allotments on behalf of the thousands waiting. The banner was then combined with larger sections and ‘dug-in’ on land owned by supermarket giant Tesco in Liverpool. We strimmed, hoed, and then laid the seed paper on an area the size of a standard ‘10 pole’ allotment plot (10x25m), then covered it in 4 tonnes of compost. The paper was made with White Clover, Red Fescue, Brown Mustard, Grazing Rye Grass and Sunflower, to support phytoremediation of the land and act as green manure. The act of land reclamation sought to demonstrate how unused sites may be cultivated and used as allotments. The seed paper also included ash from an area of scorched Amazon rainforest, gathered by activists. The use of this as a material dug into the earth close to Liverpool’s port was a reminder of the UK’s reliance on imports of soya for meat and dairy production from South America, where it drives deforestation and human rights abuses. The project received nationwide exposure and we hope contributed in a small way to promoting the development of allotments which have been shown to support physical and mental health and wellbeing, community cohesion, and biodiversity.

Situated Knowledges & Commoning

The Grass Was Taller Than Me film is very much an outgrowth of the above work, including as it does interviews with people on Elder Stubbs Allotments, but also featuring other greenspaces in and around Florence Park. Ganga and Kajol who I interviewed for the film both have plots just a few metres from my own plot, and my daughter attended Flo’s Nursery, which also features. However, it should be noted that proximity and familiarity, is also something to be questioned, especially when particular privileges play a role, and here I situate myself as a white, western, middle class, male, human. An important catalyst to my practice and learning regarding situating my privileges, and how to listen to and advocate for others within my work, is Donna Haraway’s concept of ‘situated knowledges’¹ which demands, as my friend Monika Rogowska-Stangret writes, ‘a practice of positioning that is about carefully attending to power relations at play in the processes of knowledge production’.

To connect situated knowledges to situated ecologies, suggests ways and means of how we might live with and support human and more-than-human life-forms and ecologies, which have been the subject of systematic oppression, destruction, and exclusion. As Nobel Prize winner Elinor Ostrom showed, natural resources can be jointly shared and cared for in a way that is both economically and ecologically sustainable if people work together to develop rules and act ‘in common’.² The inspiring places, people, plants, and ecologies, who tell their stories in The Grass Was Taller Than Me present local, situated, affirming modes of being and organising that cultivate common ground between old ways and old lands, and new paths, new possibilities, new growth.

This blog was commissioned by Modern Art Oxford to reflect on the themes of the Situated Ecologies off-site programme.

¹ Donna Haraway, ‘Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective’, Feminist Studies, Vol. 14, No. 3 (Autumn, 1988)

² See for example: Ending The Tragedy of The Commons | Elinor Ostrom | Big Think, YouTube, 2012

For a longer co-authored essay by Sam Skinner and Mirko Nikolić which references some of the ideas discussed above see the essay ‘Community’ published in Philosophy Today (2019).