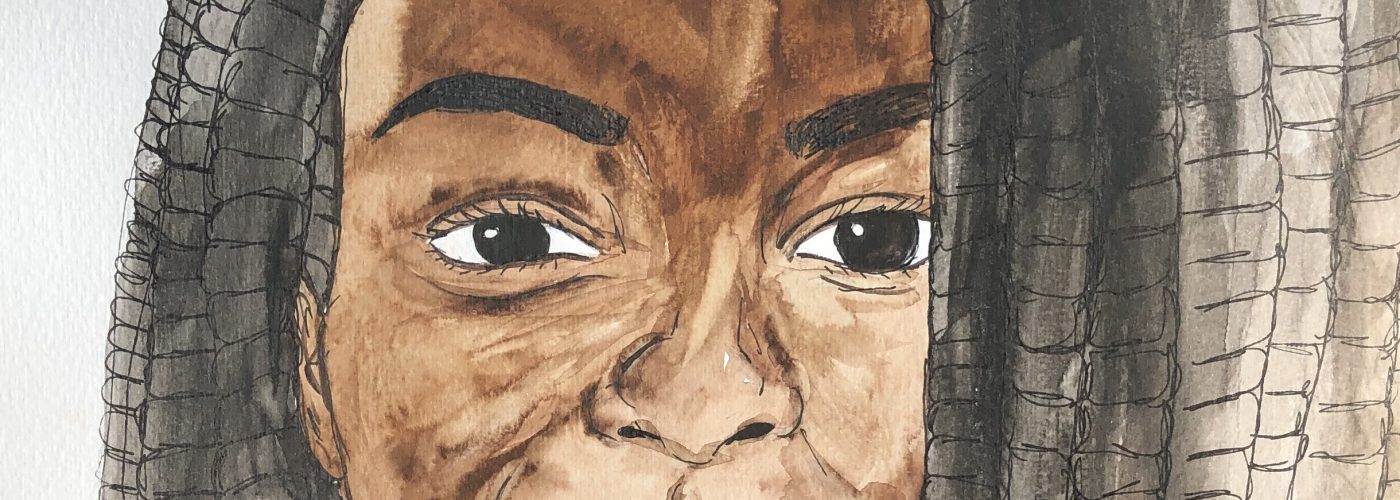

As a Senegalese woman who has never resided in her home country, artist Khadija Cecile Niang’s work explores her feeling of being disjointed from her culture. In recent work, currently on display in her exhibition It’s Not Just Hair, what began as a way for Khadija to reflect on her own personal relationship with her hair, has become a celebration of the bond between Black women through their shared experience. Portraits of Black women, combined with their conversations, recorded across different continents, reveal common experiences in spite of cultural divides.

Inspired by the themes of Black History Month 2020 – celebrating in particular the histories and achievements of Black women – Khadija writes about her experience of making the artwork for her exhibition It’s Not Just Hair in the current climate.

Words and images by Khadija Cecile Niang.

I was always hesitant to create work about myself, having had a limited idea of what it meant and could look like. I thought it would end up being narcissistic and I struggled to see how anyone would see themselves in work about me. Throughout my art course, I thought it would be more valuable to focus on “themes” and messages I could loosely relate to.

In Emma Dabiri’s Don’t Touch My Hair, she states: “I am often struck by the points of shared experience between black women when it comes to our hair, despite the fact that we might be continents apart”[1]. This quote brought the most significant shift in my art practice. What began as a self-reflective process grew into something bigger than I expected.

Dabiri’s exploration of the bond between black women inspired me to create a final piece which celebrates my relationship with other black women through our hair. Through interviews with friends and family, I felt a deep sense of belonging. Despite having different upbringings to many of my friends, having grown up living in different countries, we were all in some way linked through the experiences we’ve had (both positive and negative) in relation to our hair.

“Black hair is amazing. There are so many different things we can do with our hair. But more than that, there’s the history that is in our hair.” – Tega

(Our Hair by Khadija Cecile Niang, 2020)

Another significant quote from the book that impacted me was this one:

“Depending on the style and the size of the braids, an entire head of hair can take a long time – hours, even days – to complete. I’m reluctant to describe this process as time-consuming because I’m keen to disrupt our deeply engrained (yet recent and culturally specific) myth of time as a commodity. It makes a lot more sense to imagine braiding as a social time during which the business of living is conducted. It is a process that brings people together and facilitates intergenerational bonding and knowledge transmission.”[2]

Dabiri explores how in western society, spending time on your hair is seen as an unproductive use of time. She compares this to how invaluable this time was in pre-colonial West Africa, and specifically Yoruba culture. Having read that, I felt lockdown was a bit of a blessing in disguise for my relationship with my hair. It gave me the opportunity to reassess what I deem valuable in my time. I started to see styling and maintaining my hair as a form of self-care rather than as an inconvenience. I also took the time to learn how to braid my own hair which I have never done before, which means I can now also braid my three younger sisters’ hair.

Without having read this book, and had the hair salons remained open, I wouldn’t have taken the time to reflect on these things. My family lives abroad, so it was especially touching to create that sense of “intergenerational bonding” which Dabiri writes about. This was the first time in several years that we’ve all been together for so long and had the time to bond with each other over hair.

“When it comes to my hair I feel a strong sense of community.” – Fama

(Our Hair by Khadija Cecile Niang, 2020)

With the Black Lives Matter movement being drawn to everyone’s attention during lockdown, it felt like a significant time for me to be exploring this specific subject matter. Lockdown made things feel incredibly heightened, and the media and public attention were simultaneously thrilling and exhausting. Exhausting to be constantly reminded how much progress remains to be made, thrilling because it felt like Pandora’s box had been opened.

All the everyday discomforts that as black people you often dismiss, were finally being listened to, had a platform and had value, but it is nonetheless exhausting to feel like the world is only just waking up to things you’ve been aware of for so long. The voices of black women are often overlooked, so this piece feels more important to me than ever, as black women are at the forefront, with their stories and voices the pure focus.

“Growing up I was told my hair needed to be straight. Or it wasn’t done yet. Like an un-baked cake.” – Naomi

(Our Hair by Khadija Cecile Niang, 2020)

As a black woman, having a safe space to feel like yourself is valuable. Examining this specific part of my identity with a magnifying glass has allowed me to unpack so much which has actually made me feel more secure in myself. It has also made it clear that I have a strong community I can turn to, of women who are going through similar experiences and with whom I don’t feel the need to explain or justify the reasons I feel a certain way.

A year ago, I couldn’t imagine creating art which would allow a representation of myself to be dissected by an audience. Whilst this fear still remains, the benefits I’ve discovered from creating this work immensely outweigh the fear.

–

[1] Emma Dabiri, Don’t Touch My Hair, (London: Allen Lane, 2019), p. 23

[2] Emma Dabiri, Don’t Touch My Hair, (London: Allen Lane, 2019), p. 48

Images: Khadija Cecile Niang, It’s Not Just Hair 16; 6; 3; 18; 7; 15, 2020

Click here to follow Khadija’s work and practice.