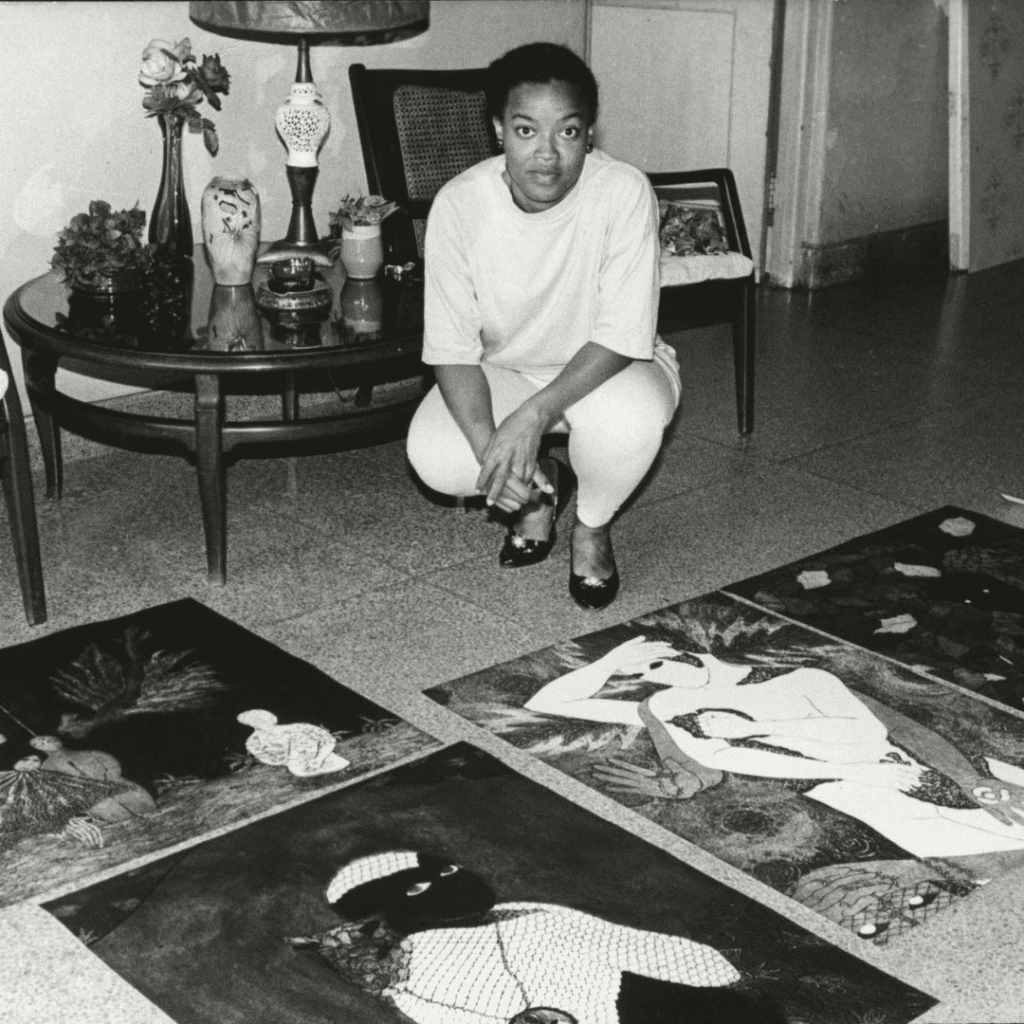

Belkis Ayón’s journey into the world of Afro-Cuban mythology began during her time as a high school student at San Alejandro. While researching the Yoruba and Kongo cultures, she stumbled upon El Monte (1954), a book that introduced her to the Abakuá , an all male secret society.

The Abakuá mythology was largely untouched by artists, which piqued Ayón’s curiosity. She became fascinated by their symbolism, particularly the society’s use of graphic signatures that spoke to her visually. Her research led her to the story of Sikán, a pivotal figure in the founding myth of the Abakuá.

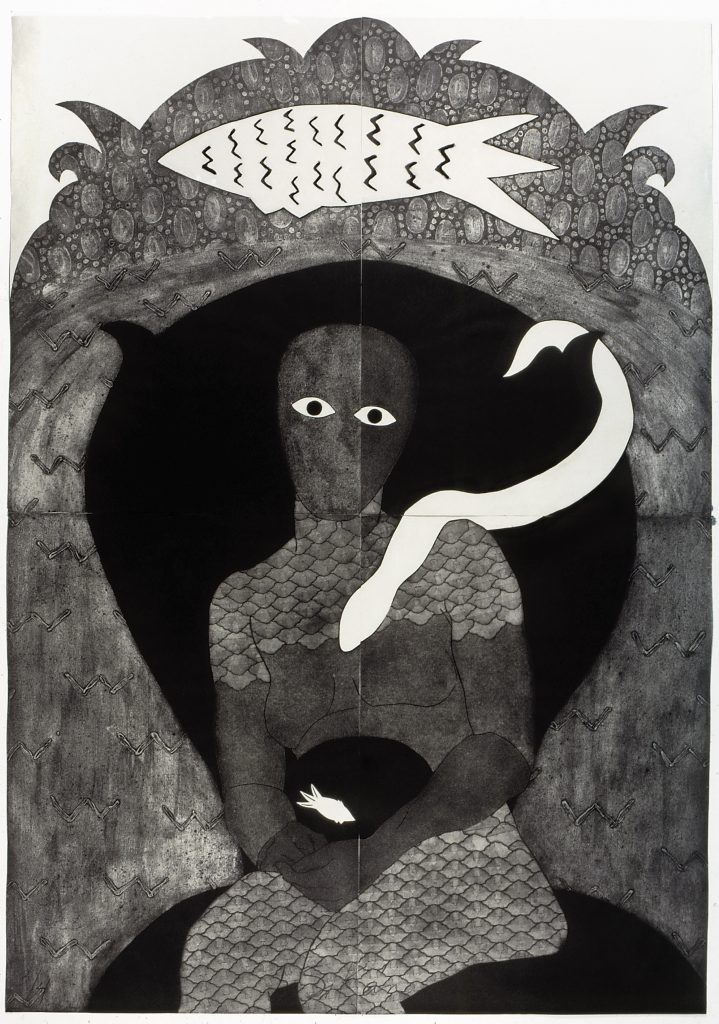

According to the Abakuá legend, Princess Sikán, while collecting water from a river, unknowingly traps a sacred fish (Tanze) in her jug. This fish is believed to be the reincarnation of an old king, and anyone who possesses it would gain great power and prosperity. However, women are not allowed to hear the mystical sound the fish makes. When the tribe’s diviner realises the fish is missing, Sikán is discovered with it. Fearing the fish’s power is now within her, the men of the tribe decide to sacrifice Sikán. The murder of Sikán risked silencing the sacred voice forever, but following the ritual sacrifice of a goat (Mbori) the voice was recaptured in the animal’s skin which was then stretched to form the surface of a sacred drum (Ekwé). The drum, now infused with the sacred voice and Sikan’s knowledge, becomes the most sacred object in the Abakuá tradition. It’s believed that through her sacrifice, her spirit is transferred into the drum, allowing the Abakuá members to access the powerful voice and presence of Tanze during rituals.

Ayón never intended to reproduce and perpetuate the Abakuá myth exactly as it was. Instead, she sought to synthesise its aesthetic, visual, and poetic elements, adding her own interpretation and inviting the audience to add theirs. The myth serves as the source of Ayón’s creativity, but the body of work she creates is something new, timeless and universal.

How does it make you feel? How do you interpret Ayón’s mythical works?

Ayón repeatedly focuses on the emotions and struggles of Sikán in her artworks, often depicting her holding the hollowed-out gourd she uses to catch the sacred fish Tanze and with scales on her skin, reminiscent of fish or snakes. Sikán became the controversial representation of femininity in the very masculine and patriarchal world of the Abakuá. She is a complex mythological character, who is venerated as the symbolic mother of the brotherhood because her discovery gave power and primacy to men and to her people.

In a 1988 manuscript, Ayón reflected on her connection to Sikán, writing, “She is like me, and she lives through me in my restlessness, as I instinctively search for an escape.” This sense of identification extends into the symbols Ayón uses; in a 1999 interview with journalist Jaime Sarusky, she explains, “the snake is forever her companion. It can be threatening, protective, or simply company for her. Likewise, in concert with that idea, I also use the snake as a phallic element.” Through these nuanced choices, Ayón reveals Sikán as a reflection of her own inner world, navigating themes of power, gender, and identity.