Ballet and Storytelling in the Archive

By Ambrose George Ellis-Keeler.

The Deadly Grove

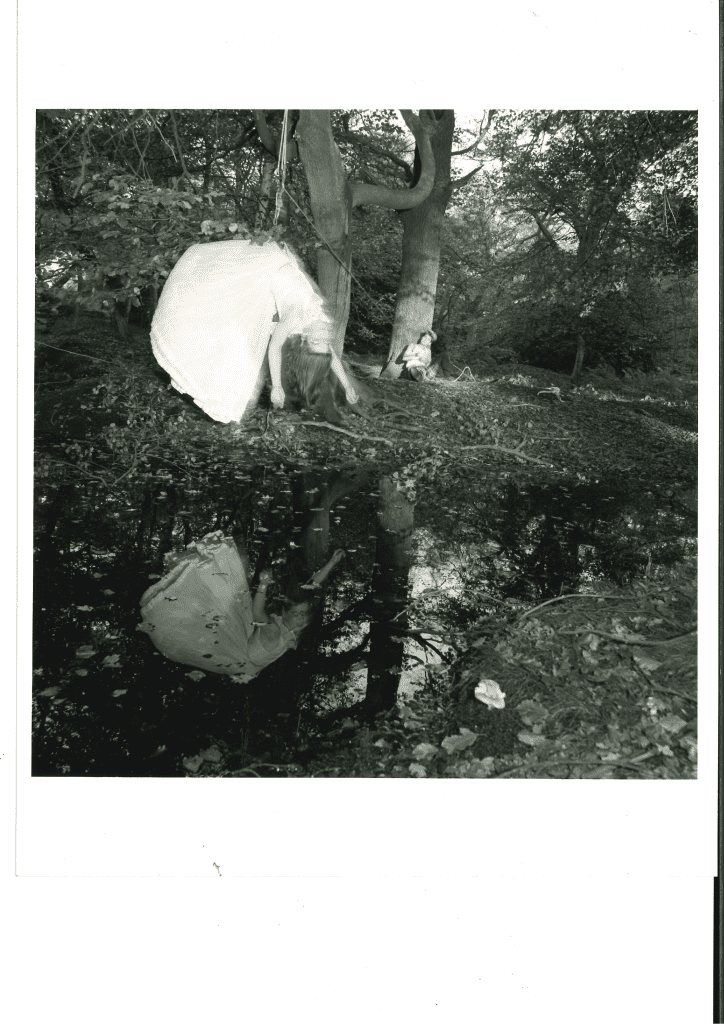

As I open up the mysterious box from the archive not knowing what’s inside, labelled vaguely as dance, each folder inside labeled with different titles, meaning nothing to me as context is removed, one labeled ‘The Deadly Grove’ calls out to me. I open the dusty pale yellow folder to be greeted by film images of black scary monster-like figures, it feels like treasure, my brain trying to fill in gaps of missing context. As I riffle though the folder one article after another, pieces of information start to form more and more of the goings on of this performance. Within the folder are two original black and white photographs taken before the performance, in woods, one of which features in all of the articles and on the promotional fliers. A ballerina hanging from a tree being via a wire from her pelvis, while a male figure in the background holding another wire seems to be controlling their movement, trapping them. The ballerina appears limp in a ghostly white gown over a large puddle containing their reflection, making them seem as if they’re falling through a portal or floating in water. This imagery has a visual connection to ‘Ophelia’, a painting by British artist Sir John Everett Millais, in which he depicts Ophelia singing while floating in a river just before she drowns. The scene is described in Act IV of ‘Hamlet’. The image provides an eerie and unsettling aura which sets the tone for the performance. As it reads on the promotional pamphlet, “At night, in the forest, in a walking dream, in a place you half remember but have never been to before, there you will find… the deadly grove”, providing a mysterious and peculiar hint of what’s to come.

Titles of various articles within the archive read ‘Don’t go into the woods’, ‘Forest fear’ and ‘Poetic exercise’. As I read in depth the number of documents piecing together all the information, the story begins to form. The ‘total environment for an exploration, for an exploration into the psychological core of legend and fairy-tail’ comes to light for me, a review from the Guardian by Cordelia Oliver. Laura Ford and Annie Griffin present ‘The Deadly Grove’, Ford producing the set and Griffin performing with a cast of ten untrained ballerinas. “Four large threatening prehistoric beasts, sculpted by Laura Ford, dominate the scene and provide precarious cover behind which cower the classically-attired ballerinas.” (The figures from the film are found!) This piece is inspired by Giselle, mainly the group of characters the Wilis. Giselle is a young peasant girl who falls in love with a disguised nobleman named Albrecht. When he was revealed to be a nobleman already engaged to another, by his rival Hilarion, Giselle goes mad and dies of heartbreak – or in some version of the story kills herself. After her death, she is summoned from her grave into the vengeful, deadly sisterhood of the Wilis. They are the ghosts of unmarried women who died after being betrayed by their lovers and take revenge in the night by dancing men to death by exhaustion. It’s evident that Giselle has very traditional notions of classical ballet. Those which are structured with an exclusionary mindset that projects a very specific vision of a ballet dancer as female, white, at peak fitness, flexible, hetrosextual and able-bodied.

Another three original black and white images taken during the performance provide a very small glimpse to the happenings within this performance. One image shows Griffin, in a black suit jacket, buried in the earth with daffodils planted around. One male dancer dressed in a classical white gown, three more female dancers and another male dressed in a suit gathered around, looking over Griffin. The other images show the humor and disturbing nature of the performance. This illustrates the subversion of heteronormative desirability and challenges the power dynamic of the balletic idea of female victimisation within the performance. Especially in conversation with the story of Giselle where the victim becomes the predator, where here ‘men and women form and reform images of each other’ which results in ‘a frequently funny series of confrontation between the sexes’, as two different articles suggest. In relation to sculptures Griffin suggested ‘we were expecting them to be male but they’re not. “They’re bit bear, bit of a dinosaur”. Which is an intriguing piece of information which further contributes to the story, where the male figure has become monstrous and continues the rhetoric of confronting the stereotypes of dance.

To experience this performance though the archive instead of via the internet is a revolutionary experience. Within the ballet and dance universe these critics are often buried, or unexposed, so to see past artists bring this into the gallery space is eye opening because I make similar criticisms in my work. Being a Trans/ Queer person within ballet space, as well as a wheelchair/mobility aid user, simply existing within this space and putting myself in the spotlight challenges the typical and expected narratives. This is before even adding my performance flare on top!

Operation Swan Lake

From the past archive to what the future archive may hold. What will be left after Susan Triesters’ exhibition? What narrative will it hold for future generations? Who searches not knowing what they will find, what story will it hold? Treister’s website in itself is a massive digital archive of her work. One project within her complex narrative web which has taken my interest is within the world of Rosalind Brodsky’s time-travel, Treisters’ alter-ego. Particularly ‘Operation Swan Lake 2028-2029: Research project- #PRN/33 Operation Swan Lake.’ Within the series of works that are a part of this project, particularly the video documentary, the story-telling throughout completely immerses you in the world of Brodsky. Where the lines of reality and fairytale become blurred. Operation Swanlake takes place in the future. In the words of Treister, through “utilising the harnessed energy of a black hole located in the constellation Cygnus, Operation Swanlake begins in 2028 as an attempt to develop audio frequencies capable of communicating with the universe. Hypothesising a connection, substantiated through alchemical research, sonic components were initially developed using retrieved recordings of swans from specific historical periods and global locations…transmitted a series of complex audio frequencies throughout the universe.”

(https://www.suzannetreister.net/suzyWWW/TT_ResearchProjects/OP-SwanLake.html)

The narrative sewn about ballet within this documentary brings a completely new perspective to the story of Swan Lake and completely emancipates ballet from the dance world and the expectations that come with traditional ballet stories. This is a new way of bringing ballet into the space of art and science, which I haven’t come across before. You are taken through a journey where the audio frequencies picked up from the first performance of Traskosky’s Swan Lake are used to weave a very convincing narrative between the audio frequencies of different works of art, theatres and swans in order to ‘communicate with the universe’ using ’Swanlake sonic missile’. How does this translate to a physical archive? This digital documentary could be translated into stills, the monologues over the video, possibly transcribed, drawings and sketches of the operation mapping, photos of physical exhibition, so many possibilities! To be able to time travel to the future like Brodsky, to see how this story would be pieced together for those delving into the archive would be truly fascinating.