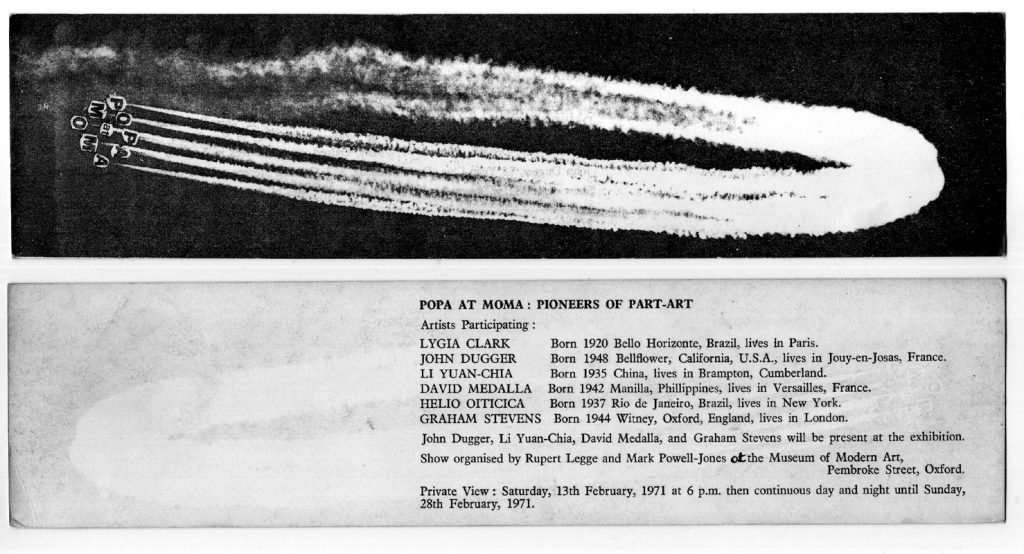

Popa at Moma: Pioneers of Part-Art opened and closed in a single evening at the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in Oxford in 1971.

MOMA was a much younger organisation than either the Tate or the ICA, having opened only in late 1966. Its founder, Oxford architect Trevor Green, intended it to house England’s first modern art collection, but it quickly evolved into an alternative space rather than a museum. It was daringly housed in a reclaimed brewery building in a ‘dismal, depopulated street’, and became known for experimental exhibitions of environments and kinetics by young artists and collectives.

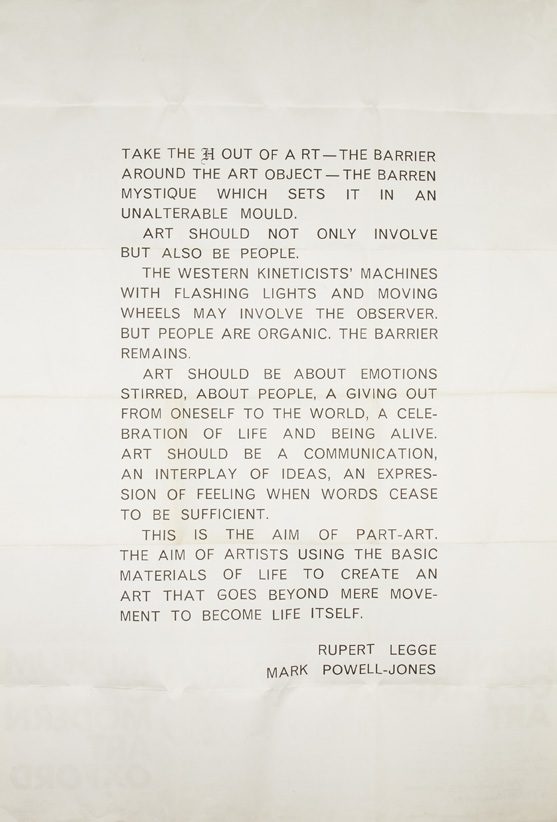

Popa at Moma was unusual in having been conceived and organised by undergraduate members of the Oxford University Art Club (OUAC). Rupert Legge and Mark Powell-Jones applied to the ACGB in early 1970 for a one-off grant of £120.36. Their proposal, originally entitled Art of the Id, made ambitious claims for a new genre of art, which could uniquely stimulate the direct interplay of ideas between the artist and the observer, culminating in a spontaneous burst of energy, a desire to respond and give back directly to the work.

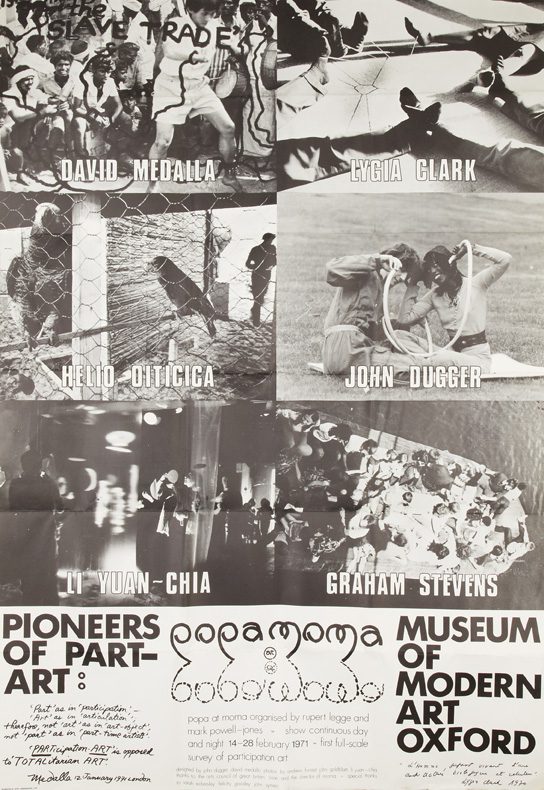

Duly awarded their £120 on the condition that the exhibition be hosted by MOMA, the two began a process of research to uncover artists working in a suitable vein. While not (yet) describing themselves as ‘part-artists’, a remarkable international group associated with the defunct Signals Gallery in London was discovered by the students and tapped into. Signals was situated on Wigmore Street from November 1964 to October 1966, and was run by critic Guy Brett and artists David Medalla, Marcello Salvadori, Gustav Metzger and Paul Keeler. During its short existence the gallery produced an ambitious news bulletin and a series of important exhibitions that brought together artists such as the Brazilians Lygia Clark and Hélio Oiticica, Li Yuan-Chia from China, and other kinetic artists from Europe and the United States. All the artists selected for Popa at Moma – Clark, Oiticica, Yuan-Chia, Medalla, John Dugger and Graham Stevens – had been connected with Signals and continued to associate with each other thereafter. The exhibition was heavily influenced by Brett’s 1968 book Kinetic Art; Brett, who by the late 1960s was art critic for the Times and regularly reviewing MOMA exhibitions, also lent works for the show. As Medalla wrote to Ibsen in January 1971, ‘everybody I spoke to in London thinks it’s a coup for MOMA oxford to stage the first show devoted entirely to part-art’.

After a chaotic organisation period that required the intervention of Sir John Pope-Hennessy at the Arts Council, an exhibition spanning all three floors of the warehouse building opened for a Saturday evening preview on 13 February 1971. The works included touchable installations, large pneumatic structures, and wearable objects such as capes and masks designed to heighten awareness of the human body.

At the opening the largely undergraduate audience apparently took such statements at their word and, buoyed perhaps by the complimentary wine and the energising effects of bouncing on Graham Stevens’s large inflatables, began to physically engage with works of art in ways unintended by their creators. Medalla and Dugger, who arrived at the exhibition three-quarters of an hour late, were indignant at what they saw. Medalla, a Buddhist, objected to the serving of wine at the preview and, according to the Birmingham Post, ‘told the audience: “You are all Philistines. People should know how to treat works of art.’ Although opinions differed as to the degree of real damage done, Dugger told journalists that he had seen visitors beating his works against a wall, adding ‘I have not found this sort of reaction anywhere else but England and nowhere as violent as in Oxford’. Medalla and Dugger withdrew their works from the exhibition immediately, while Stevens pulled out the following day. Sensational headlines such as ‘Art Preview Ends in Uproar’ and ‘Artists Call Spectators Philistines – And Quit’ appeared in local and national newspapers, the latter accompanied by a photograph of Medalla dressed only in a sarong, knee-deep in what appears to be a pile of debris. The publicity that the event attracted was completely without precedent in the museum’s short history, as the narrative potency of the events at Popa at Moma proved assimilable to a variety of narratives about the plight of modern culture.

In some cases journalists exaggerated the extent of the mayhem through a lack of understanding of the original works. Graham Stevens’s inflated sculptures were not ‘severely damaged by people jumping on them’, for this was their intended function, but because of technical difficulties with his blowers on the night of the opening. Similarly, what may appear to be debris in press photographs of Medalla was in fact the chains and polythene that made up his work Down With the Slave Trade being dismantled by the artist. Legge and Dugger have both since downplayed the recklessness of the opening-night visitors, blaming the misunderstanding of a well-meaning crowd in the absence of the artists’ instruction. Peter Ibsen’s wife, Antoinette, has even speculated that Medalla planned to withdraw his works from the show to secure maximum publicity. Despite differences of interpretation, however, there was an agreement among those present that participation had turned, unmistakeably, into over-participation.

Taken from Tate Papers: ‘Everything Was Getting Smashed’: Three Case Studies of Play and Participation, 1965–71, by Hilary Floe: https://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/22/everything-was-getting-smashed-three-case-studies-of-play-and-participation-1965-71