In this post we take a closer look at the life and work of Zuni potter and weaver We’wha (1849-1896), whose work and life story helped to inspire Mariana Castillo Deball’s exhibition Between making and knowing something.

Deball was inspired by the archives of several women anthropologists and makers held across the Pitt Rivers Museum collection and the Smithsonian Institution collection in Washington D.C. Explore the stories of other pioneering women on our blog.

–

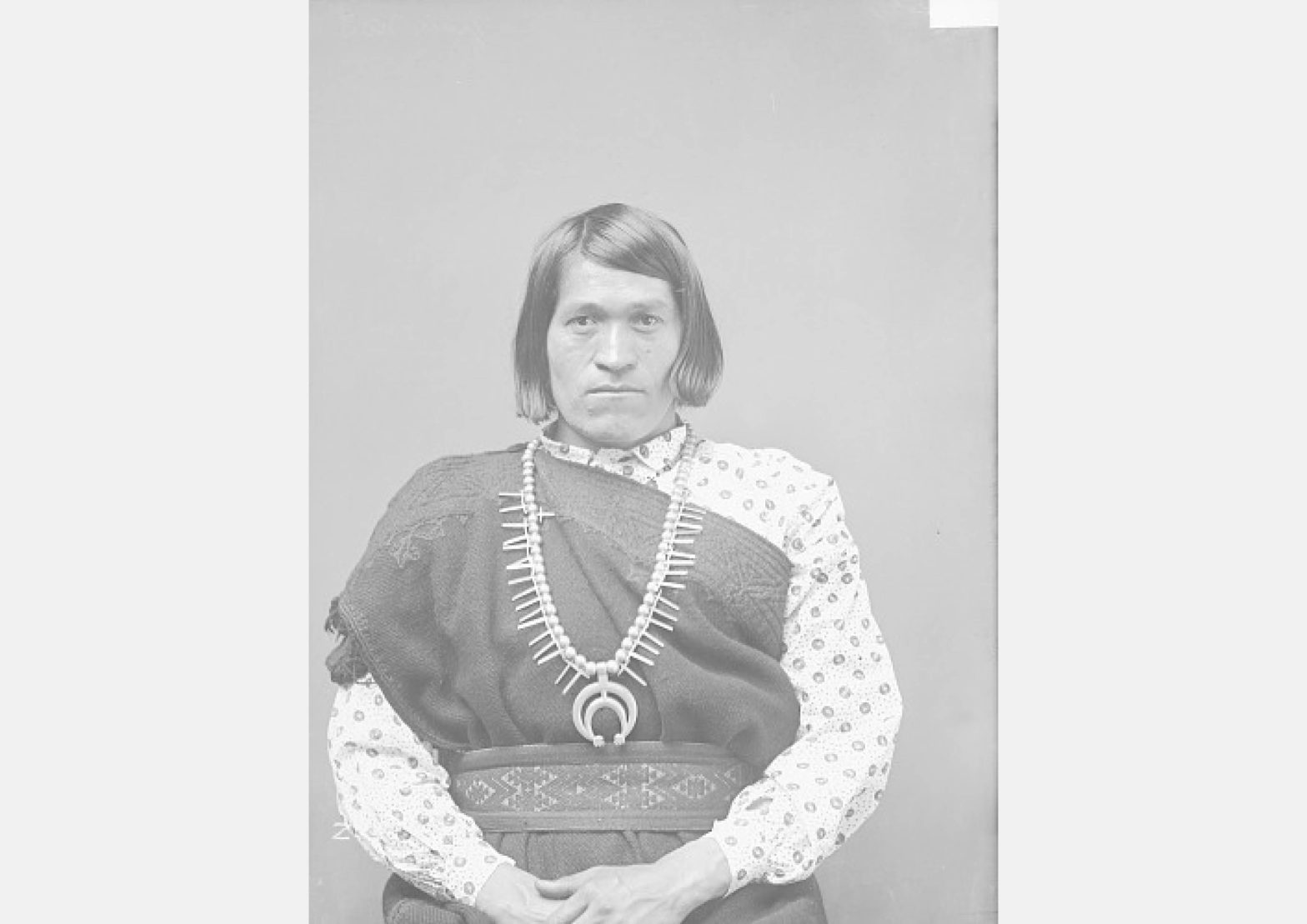

We’wha (1849-1896)

We’wha had a particular position in Zuni society as an lhamana or ‘two-spirit’ – the third gender or ‘man/woman’. Ihamanas are male-bodied people who take on the social and ceremonial roles usually performed by women in their culture.

The Zuni are a Native American Pueblo people native to the Zuni River valley in Western New Mexico.

The ceramic pots hanging in Deball’s exhibition were hand-made by the artist, and modelled on original vessels made by We’wha, with Deball reproducing painted designs and pottery techniques developed by the Zuni.

The anthropologist Matilda Coxe Stevenson met We’wha while conducting fieldwork in the Zuni Pueblo in the late 19th century. In 1886, We’wha was part of the Zuni delegation to Washington D.C, hosted by Stevenson, and she stayed with Stevenson and her husband in their home for several months.

We’wha produced many objects there, while Stevenson took photographs of her working methods, including We’wha demonstrating Zuni weaving on the lawn of the National Mall.

We’wha’s broad and unique artistic talent, including her skills in making pottery, looms, prayer feathers, woven belts, and textiles, was quickly recognised.

All the items We’wha had made there were reportedly added to the Smithsonian collections of the US National Museum, now the National Museum of Natural History.

Unfortunately, if these objects were added to the collection, they were never attributed to We’wha, resulting in a significant gap between the accounts of We’wha’s visit and her material legacy at the Smithsonian Institution.

In her exhibition, Deball brings to life the personal history and cultural knowledge of this remarkable storyteller by faithfully reproducing We’wha’s unattributed, but artistically distinct, ceramic designs.

Deball shines a light on We’wha’s technical skill and artistic imagination in an attempt to expose and overturn We’wha’s historic erasure.

Explore the stories of other pioneering women who inspired Deball’s exhibition. Click here to read the extraordinary story of Maori guide and anthropologist Makereti, and click here to read about British anthropologist Elsie McDougall.

A note on pronouns: In many of the first historical accounts, We’wha was described using feminine pronouns. In the late twentieth century, however, masculine pronouns were used. In writing about the material contributions by We’wha in the Smithsonian Institution collection we have chosen to use feminine pronouns to correspond to the terminology and perceptions of We’wha’s time frame.