In this post we take a closer look at the life and work of American ethnologist, geologist and explorer Matilda Coxe Stevenson (1849-1915), one of the women who inspired Mariana Castillo Deball’s exhibition Between making and knowing something.

Deball was inspired by the archives of four women anthropologists and makers held across the Pitt Rivers Museum collection and the Smithsonian Institution collection in Washington D.C. Explore the stories of the other pioneering women on our blog.

–

Matilda Coxe Stevenson (1849-1915)

Born in Texas and raised in Washington DC and Philadelphia, Stevenson was an ethnologist, geologist and explorer. She was the first woman anthropologist to study the American Southwest. She was also the first (and for a long time the only) female anthropologist hired by the US government. She founded the Women’s Anthropological Society in 1885.

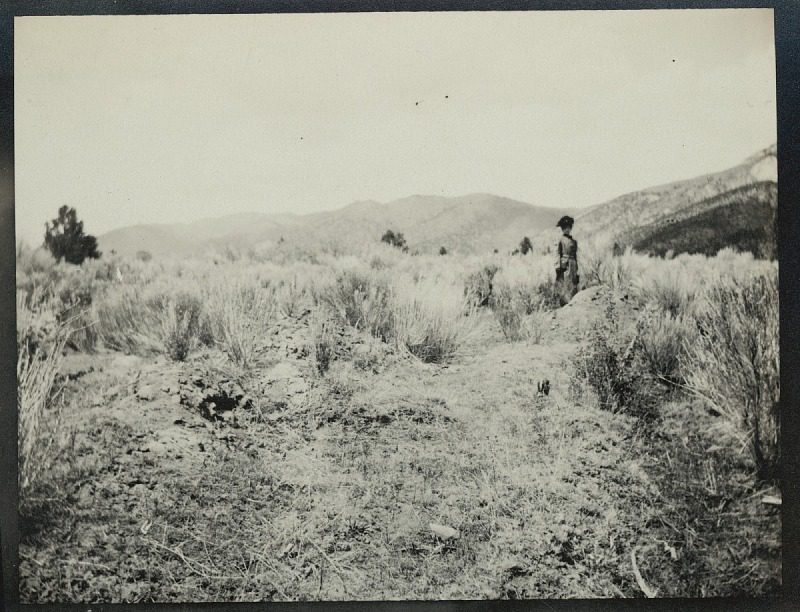

At 23 she married James Stevenson, a geologist with the US Geological Survey of the Territories. From 1872-1878, Stevenson joined him on geological surveys to Colorado, Idaho, Wyoming, and Utah, helping him (working for free) by compiling geological data.

After her husband’s death in 1888, she was hired by the Bureau of American Ethnography to organise his notes, going on to become their first regular female staff member.

From 1890 to 1915, Stevenson carried out individual fieldwork in the Zuni Pueblo in Western New Mexico.

She was interested in rituals and ceremonies, but also in the activities of daily life such as manufacturing adobe bricks (made from earth and organic materials), playing games, and collecting water. She documented these actions with her camera, compiling series of photographs.

It was here that she met We’wha, a Zuni lhamana (‘two-spirit’), an exceptionally skilled potter and weaver, who would become one of the main native informants in Stevenson’s research, travelling to Washington as part of the Zuni delegation in 1886, and spending several months living in Stevenson’s home.

Stevenson was a pioneer in publishing studies on Zuni life, and collecting Zuni artefacts for the Smithsonian Institution collection. However, she also remains a controversial figure among the Zuni people (and contemporary anthropologists) because the documentation of Zuni rituals is forbidden. This is one reason why her photographs are rarely published today.

Delve deeper into the complex and unsettling history of anthropology and exploration via our Instagram page next week as we share insights from our exhibition tour with Uncomfortable Oxford. We will link to the tour here when it goes live.