If you’ve visited our current exhibition Samson Kambalu: New Liberia you’ll know that the artist gets lots of inspiration from his own life and experiences.

From his childhood in Malawi, to his life as an Oxford University professor, we’ve put together a list of 6 things you might not know about Samson Kambalu and his creative inspirations.

Samson Kambalu was born in Malawi in 1975, just over a decade after its independence from British colonial rule.

In 1975, Malawi was under the governance of Hastings Kamuzu Banda, Prime Minister and later President of the country from 1964 until 1994. Two years after being appointed Prime Minister of Nyasaland (what Malawi was called at the time) in 1964, Banda proclaimed Malawi a republic with himself as president. By 1970, Malawi had become a totalitarian one-party state. Banda presided over one of the most repressive regimes in Africa, with political opponents regularly tortured and murdered.

He attributes his spirit of defiance partly to his father’s warnings as a child.

In Jive Talker (2008), Kambalu remembers his father’s warning: “Don’t let the tourist take your picture, or next thing you know, you are in an Oxfam appeal.” When a Scottish tourist orders him to remove his shoes for a photograph, Kambalu resists. He gives in, but poses with his hands on his hips, “figuring that she couldn’t use that picture for an Oxfam appeal because a hungry person wouldn’t look so full of himself”.

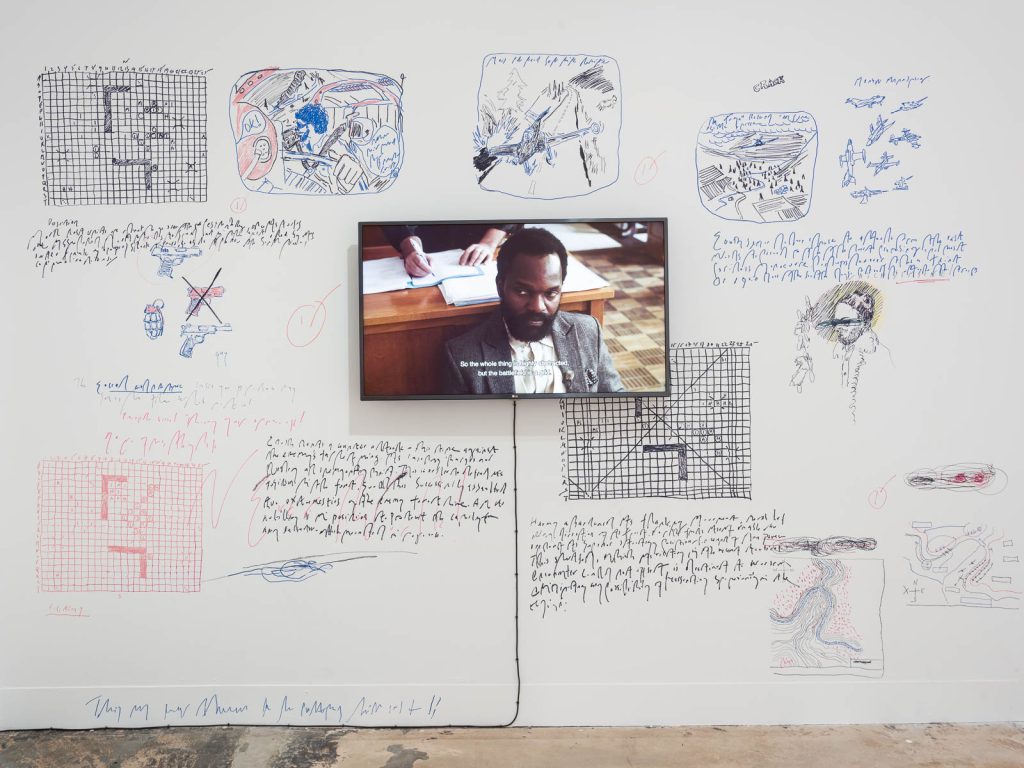

This spirit of defiance resonates in Kambalu’s exhibition. A central podium invites visitors to re-enact scenes from the inquiry into the Chilembwe uprising of 1915, an anti-colonial protest in Malawi. Extracts from witness testimonies give voice to the disputes around the performativity of clothes in colonised Malawi (then called Nyasaland).

Under British colonial rule, a black man could be violently punished for being near a white man without removing his hat, and sometimes shoes, to signal his perceived inferiority. Simple acts of self-respect, such as wearing your hat as you please in public, were demonstrations of personal freedom and colonial resistance.

Kambalu was a student at Kamuzu Academy, sometimes compared to Eton College.

As a child, Kambalu won a place at the prestigious Kamuzu Academy. Sometimes compared to Eton College, Kamuzu Academy was founded by Hastings Kamuzu Banda. Kambalu has described it as: “the most beautiful place I have ever been”.

In this western educational environment, he was taught of art as “superstructure, something that we did on the Sunday, we went to the museum”. Kambalu describes the contrast when he would go back to the villages: “there I saw art as infrastructure. Art was at the heart of everything.”

He staged the first conceptual art exhibition in Malawi.

In 2000 Kambalu made a work called Holy Ball, a football wrapped in pages of the Bible, and invited people to ‘exercise and exorcise’ with it at various venues, both local and international, starting with the University of Malawi’s Chancellor College. This was Malawi’s first exhibition of conceptual art. Since then, Kambalu has evolved a philosophy of life and art based on play and critical transgression.

He is a professor of Fine Art at the Ruskin School of Art, University of Oxford.

Kambalu is a professor of Fine Art at the Ruskin School of Art, University of Oxford. He is affiliated with Magdalen College, a place of learning that is almost 600 years old. His short silent film Don (2014) was filmed when Kambalu was visiting the city as a tourist, before he became a professor. Filmed in one of the Oxford colleges, it is strangely prophetic of his future as a professor, or “don” at Oxford University.

Kambalu was sued for his work at the Venice Biennale in 2015.

In 2014 the Italian Situationist Gianfranco Sanguinetti sold his archive to Yale University’s Beinecke Library. Critics saw this as going against the Situationist spirit of public ownership and gift-giving. Kambalu photographed the entire archive and exhibited it at the Venice Biennale with an aim to return it to the public domain.

Sanguinetti sued Kambalu and the Biennale demanding closure of the installation, pulping of the Biennale catalogue and a fee of 20,000 euros for each day of delay. Sanguinetti did not win the case at Venice and owes Kambalu legal fees. In August 2020 the case was heard again in a Belgian court at Ostend, according to continental law regarding parody and authors’ rights. You can watch the trial as part of our exhibition New Liberia.

Click here to discover Samson Kambalu: New Liberia in the gallery.